Yeondoo Jung (b. 1969) has been in the spotlight in the domestic and international art worlds for his intriguing performance and staging-oriented photography, video, and installation works that blur the lines between fiction and reality with stories of ordinary people and historical events. Last year, he was selected as an artist for the MMCA Hyundai Motor series at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA).

Yeondoo Jung, Boramae Dancehall, 2001 ©Yeondoo Jung

Jung studied sculpture at university but has made a name for himself through his photography. His first photography work was Hero (1998). After helping a young man who had an accident while delivering a motorcycle one day, the artist became intrigued by the fact that even though he was making deliveries to local apartments, he had a dream of riding a Harley-Davidson, and this became the story behind the creation of Hero, which captures the moment of a teenage food delivery worker in the pose of an action movie star. Since then, Jung has been working on photographing the dreams and stories of ordinary people. Even if they are dreams that have not come true in reality, they remain realized in his photographs.

The artist’s first solo exhibition in Seoul, “Boramae Dancehall” (Alternative Space LOOP, 2001), was the first to showcase his attitude toward photography. Jung took photographs of middle-aged people dancing in Boramae Park and used them as wallpaper patterns to fill the exhibition space, transforming it into a dance hall. The romance that ordinary middle-aged people have been cherishing extends beyond the photograph and into the space. The artist explained that this was the first time he chose the medium of photography, but instead of trying to create a photographic work, he chose only the necessary parts of the medium and cut them down. In other words, for him, photography works as a tool for the subject matter he wants to express.

Yeondoo Jung, Bewitched #2, 2002 ©Yeondoo Jung

Yeondoo Jung, Bewitched #2, 2002 ©Yeondoo JungJung continued to focus on the dreams of ordinary people. In his representative work Bewitched (2001-), he uses a camera as a magic lamp to make people’s dreams come true for a short time, and for this purpose, he met and spoke with 13 young people from six countries. After interviewing them, he photographed them in their real life and then took a photograph of them in the same composition and pose, but with a version of their dreams realized, and placed them in parallel. The portraits of young people from different countries, such as Korea, China, and Japan, not only show individual wishes, but also reflect the social situation in different countries.

The Bewitched series was inspired by the 1960s American TV drama “Bewitched”. At the time, camera technology was not as advanced as it is today, and to capture scenes in which the show’s heroine, a sorceress, fulfills her wishes through magic, the camera would freeze whenever the main character performed a magic trick, then change the background and actors’ costumes, and film the actors in the same pose as before the camera stopped. Jung borrowed this technique for his Bewitched series as a device to visualize the hopes of young people.

Yeondoo Jung, Documentary Nostalgia, 2007 ©Yeondoo Jung

After Location and Documentary Nostalgia, which he showed at the “Artist of the Year 2007” exhibition at MMCA, Jung began to use various media such as video and film in earnest. And while his previous works were mainly based on the theme of ‘dreams’, starting with Location in 2007, he began to question the authenticity of our backgrounds through stages or scenes that mix real and fake, and made the stage he created and the work itself the subject of a full-scale experiment.

Documentary Nostalgia consists of ‘footage’ and ‘installation’ such as cameras, lights, props, and equipment used to shoot the footage. The video is presented one after another in six scenes: ‘room’, ’empty city street’, ‘rural landscape’, ‘field’, ‘forest’, and ‘sea of clouds’, and the camera shoots 70 minutes of footage in one shot without editing. In Documentary Nostalgia, filmed in the exhibition hall of the MMCA, the entire process of changing and installing backgrounds, furniture, and props is revealed.

The viewer enters a living room with a sofa and a wall-mounted PDP and watches the video made in this room, and when they finish watching the video, they enter an exhibition hall with cinematography equipment and props. This works as a device for the viewer to realize that he or she is the protagonist of this stage, which is a mixture of video and installation created by the artist.

With this work, the artist became the youngest artist to win the Artist of the Year Award at the age of 38, and the following year, in 2008, the work was accepted into the collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, where it attracted great attention.

Yeondoo Jung, Blind Perspective, 2014 ©Yeondoo Jung

Since 2014, he has been reconstructing macro narratives such as war, disaster, migration, nation, and ideology through personal narratives, myths, and folk tales, and through the language of poetry, music, and theater, paying attention to the gaps and multi-layered voices that remain uncovered in the process of organizing documentary narratives.

Presented in a solo exhibition at Art Tower Mito in Japan in 2014, Blind Perspective was set in an area devastated by the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. Wearing a VR device, the viewer walks through a corridor lined with about 16 tons of waste collected by the artist during his visit to the area.

While the outside of the VR device shows the debris of the disaster, the inside of the device shows the beautiful and peaceful town before the earthquake. In this work, the viewer experiences the overlap between the present and the past, the virtual and the real.

Yeondoo Jung, One Hundred Years of Travels, 2023 ©Yeondoo Jung

Last year’s exhibition, “MMCA Hyundai Motor Series: Jung Yeondoo – One Hundred Years of Travels,” showcased works on the theme of the Korean diaspora that traveled to Mexico in the early 20th century. Based on the records of real people involved in the history of Korean immigration to Mexico, One Hundred Years of Travels features the performances of pansori, Japanese gidayū bunraku, and Mexican mariachi music. With these three videos documenting these performances, a single-channel video with images of farmers, labor, crowds, and plants shot by the artist in Mexico is rhythmically harmonized.

The artist has traveled to Mexico three times for this work, interviewing descendants of Korean immigrants and interacting with immigrants. The artist’s method of working through these relationships serves to bring out the micro-narratives of the Mexican migration. His mixed-media works, which incorporate text, performance, video, sound, and theatrical installations, serve as visual devices to evoke the various paradoxes, contradictions, and contexts of hybridity that lie beneath the history of migration.

“I think the audience can create a macro narrative. Because the work is always as subjective and micro as possible, but when it meets the audience, it gets a macro perspective, so it’s only complete when the audience can relate to the work and be part of it, which is something that the artist can’t do alone.”

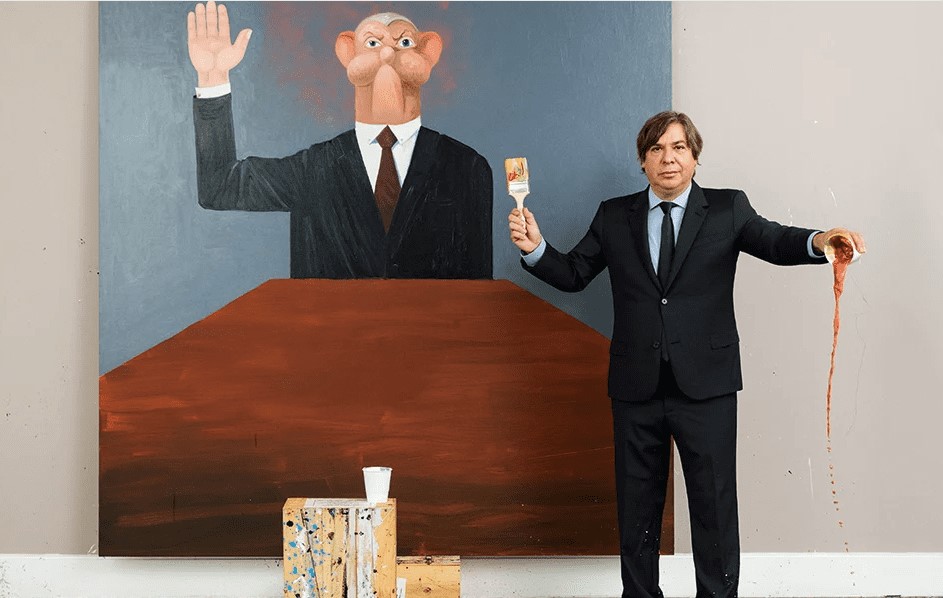

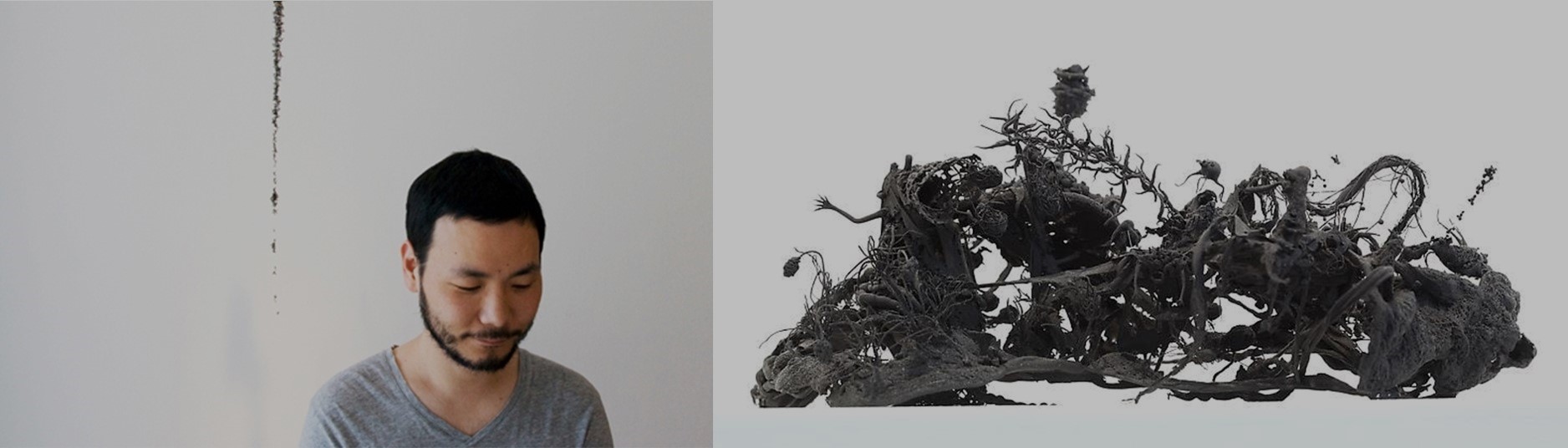

Artist Yeondoo Jung ©Kukje Gallery

Yeondoo Jung graduated from the Department of Sculpture at the Seoul National University College of Fine Arts and completed his studies at Central Saint Martins, London. He received his MFA from Goldsmiths, University of London. Since his first solo exhibition in 2001, he has exhibited his work at the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, the Gwangju Biennale, the Shanghai Biennale, and the Istanbul Biennale, and has participated in numerous solo and group exhibitions in Korea, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Japan, Taiwan, and China. In 2008, Documentary Nostalgia (2007) was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, and his major works are in the collections of the MMCA, Seattle Art Museum, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo.

References

- 정연두, 국제갤러리 (Yeondoo Jung, Kukje Gallery)

- 국립현대미술관, MMCA 현대차 시리즈 2023: 정연두 – 백년 여행기 (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea, MMCA Hyundai Motor Series 2023: Jung Yeondoo – One Hundred Years of Travels)

- 더 스트림, 역사를 다루는 태도로서의 사중주 : 정연두_INTERVIEW, 2020

- 한겨레, 소원을 말해봐, 카메라는 그의 지니, 2019.10.19

- 뉴스핌, [인터뷰] 정연두 “관람객 거시적 관점과 만나야 예술이 된다”, 2023.09.14