The

“Yoon Suk-yeol Rebellion” has ended in failure. Had this coup succeeded, it

would have undermined the values of democracy in the Republic of Korea, leading

to a new dark era where citizens’ freedoms and rights were suppressed.

Citizens

filling the entire Avenue of the National Assembly, stretching from the

entrance of the National Assembly building to Yeouido Park ⓒWikipedia

Citizens

filling the entire Avenue of the National Assembly, stretching from the

entrance of the National Assembly building to Yeouido Park ⓒWikipediaThis incident has etched

another cruel and sorrowful chapter in our nation’s history. However, it was

the mature civic consciousness and peaceful protests of the people that

thwarted this illegal coup attempt.

In the lead-up to the

impeachment vote, tens of thousands of citizens gathered in front of the

National Assembly, holding candles and chanting for the defense of democracy.

Young people wielded “impeachment support sticks” and sang K-Pop songs,

conveying messages of solidarity—a beautiful scene rarely seen worldwide.

Had this rebellion succeeded,

Korea’s cultural and artistic sectors would have faced another dark period.

Works that awaken the human spirit and prompt societal reflection would have

been suppressed, leaving only meaningless decorations and superficial pieces,

thereby draining the vitality from culture and art.

This incident prompts a

reflection on the political oppression and artistic suppression that the Korean

art community has endured in the past. Through this examination, we aim to

understand the current situation and seek directions for the future.

Suppression of Fine Arts During Japanese Occupation

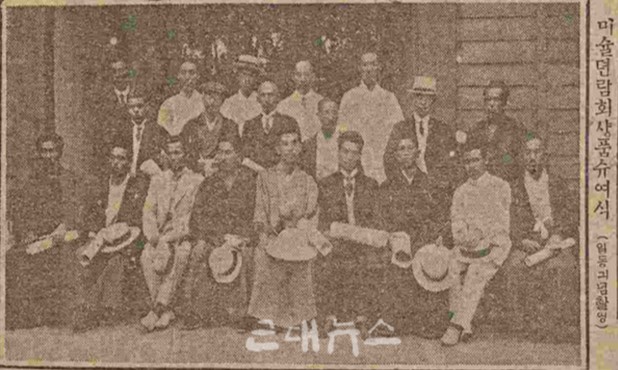

During the Japanese colonial era, Japan rigorously controlled Korean traditional art and nationalist expressions. The Joseon Art Exhibition (Joseon Misul Jeonramhoe), held annually from 1922 to 1944, epitomized this suppression. The eligibility criteria for the exhibition required participants to have resided in Korea for at least six months, effectively privileging Japanese artists living in Korea.

June

22, 1922: Commemorative photo of the award ceremony for the Joseon

Art Exhibition ⓒ Modern News

June

22, 1922: Commemorative photo of the award ceremony for the Joseon

Art Exhibition ⓒ Modern NewsUnder these constraints, Korean traditional art was systematically excluded, while works reflecting Japanese aesthetics and ideology were promoted. The exhibition became a colonial tool to regulate the art world, forcing many artists to adopt Japanese names and conform to imperialist ideologies. Others resisted through silence or reduced their activities, striving to preserve their national identity.

Female

students visiting the 1st Joseon Art Exhibition as a

group, held in June 1922. ⓒDong-A Ilbo archival photo

Female

students visiting the 1st Joseon Art Exhibition as a

group, held in June 1922. ⓒDong-A Ilbo archival photoCensorship and Repression

During Military Regimes

The regimes of Park Chung-Hee and Chun Doo-Hwan wielded anti-communist ideologies to exert tight control over artistic expression. In the 1970s, avant-garde art activities were frequently halted under the pretext of “preventing social disorder.”

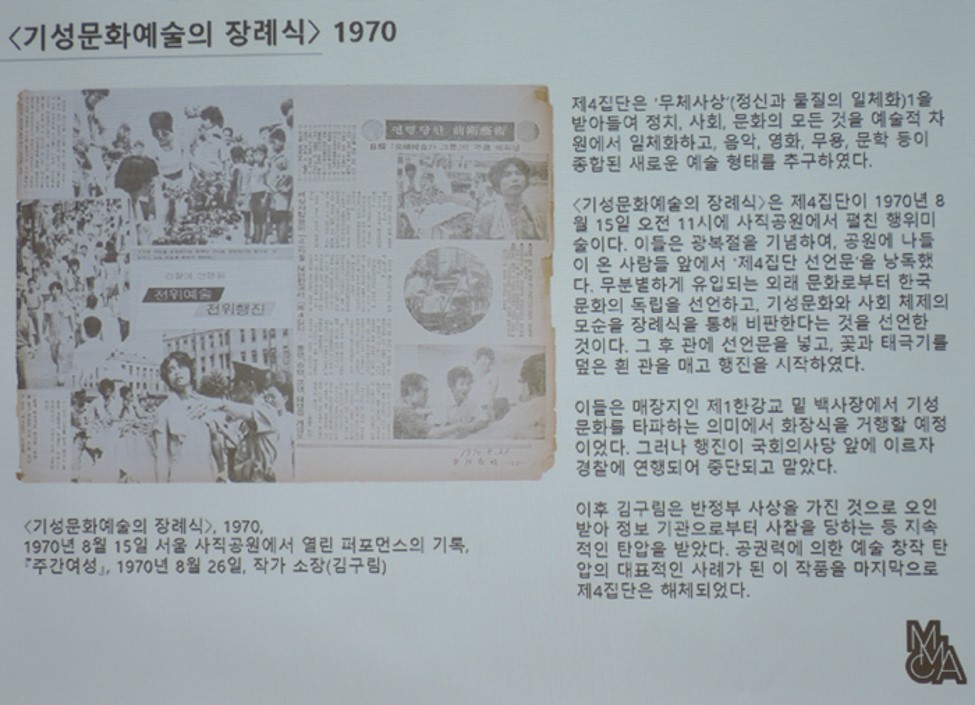

Article

content related to The Funeral of Established Art and Culture

ⓒ National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA)

Article

content related to The Funeral of Established Art and Culture

ⓒ National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA)One notable event occurred on August 15, 1970, when a group of young artists gathered at Sajik Park in Seoul to stage a performance titled The Funeral of Established Art and Culture. This performance, intended to declare cultural independence from Western influences on Korea’s Liberation Day, was interrupted as the participants were detained by police.

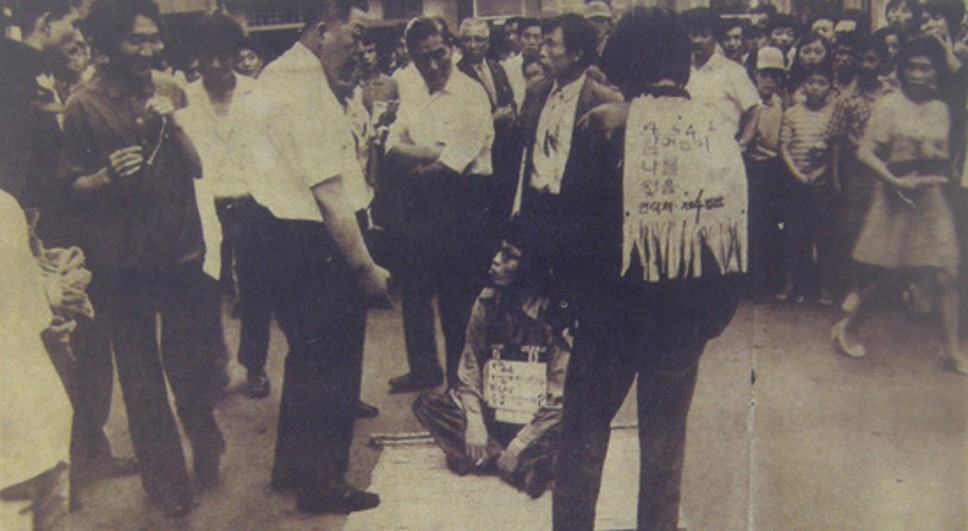

A

street performance by the Fourth Group in

Myeong-dong. While attempting to hold The Funeral of Established

Art and Culture, they were abruptly arrested on charges of

obstructing traffic. ⓒSeoul Museum of Art

A

street performance by the Fourth Group in

Myeong-dong. While attempting to hold The Funeral of Established

Art and Culture, they were abruptly arrested on charges of

obstructing traffic. ⓒSeoul Museum of ArtThe government subsequently outlawed all forms of avant-garde art, reinforcing bans on long hair and mini-skirts as symbols of societal disorder. This crackdown dismantled the Fourth Group, a collective of avant-garde artists, and its leading member, Kim Ku-Lim, was subjected to interrogation by the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA).

Kang Guk-jin, Jung Kang-ja, and Jung Chan-seung, Murder

by the Han River, 1968. Documentation of a performance held on

October 17, 1968, under the Second Han River Bridge (now Yanghwa Bridge).

ⓒNational Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) Art Research Center

Kang Guk-jin, Jung Kang-ja, and Jung Chan-seung, Murder

by the Han River, 1968. Documentation of a performance held on

October 17, 1968, under the Second Han River Bridge (now Yanghwa Bridge).

ⓒNational Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) Art Research CenterThe Rise of Minjung Art in

the 1980s

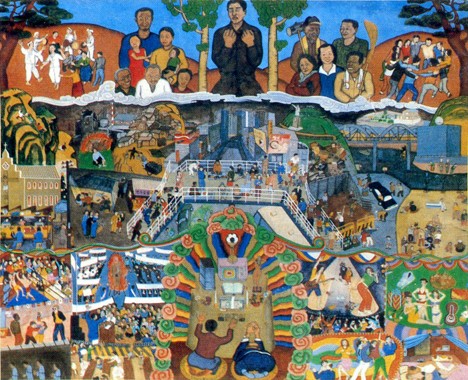

The 1980s saw the emergence

of Minjung Art, a movement intertwined with Korea’s democratization efforts.

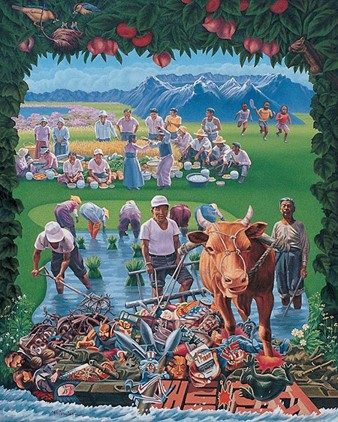

Shin Hak-Chul's Rice Planting (1987)

Focused on themes of labor, rural life, and the urban poor, Minjung Art critiqued social inequalities through murals, woodcuts, and accessible artistic formats. The political turbulence of the Gwangju Uprising profoundly influenced the movement, transforming art into a tool of resistance and activism.

Dureong, Mountain Painting, 1983, cover image ⓒDureong

Despite facing government

censorship and persecution, Minjung Art became a powerful symbol of defiance

and social commentary.

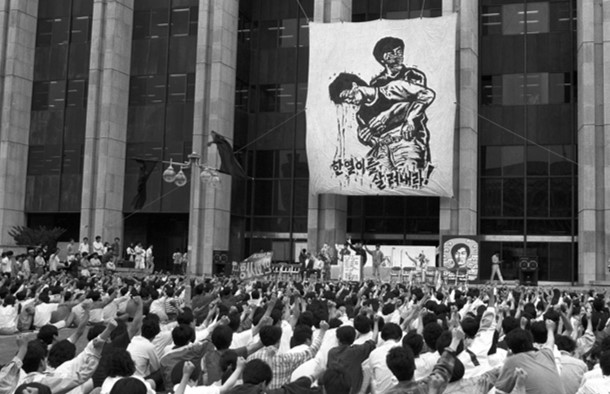

A

banner painting titled "Save Han-Yeol," installed during the memorial

service for martyr Lee Han-Yeol ⓒPark Yong-Soo

A

banner painting titled "Save Han-Yeol," installed during the memorial

service for martyr Lee Han-Yeol ⓒPark Yong-SooBlacklists in the Lee Myung-Bak and Park Geun-Hye Administrations

The Lee and Park administrations took censorship to another level with the infamous blacklist scandal, targeting artists critical of the government.

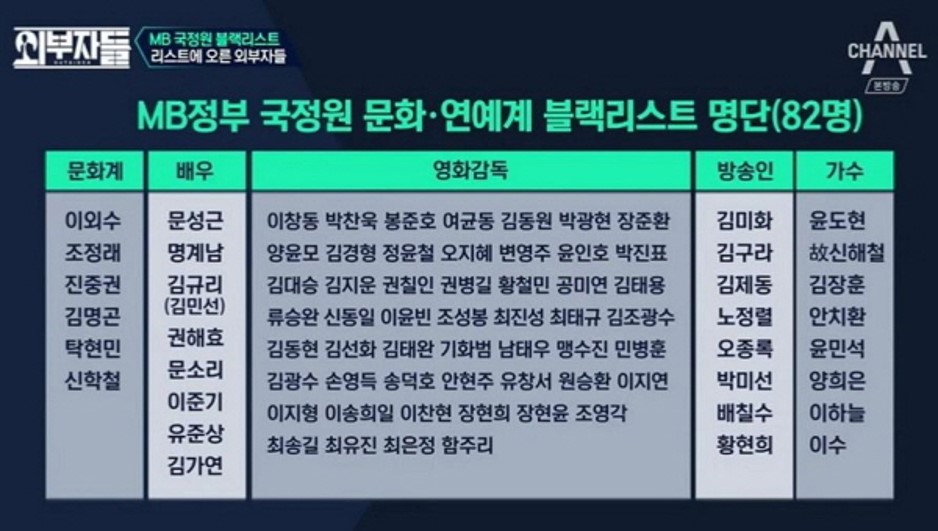

The

cultural and artistic blacklist of 82 individuals under the Lee Myung-Bak administration.

The list includes prominent novelists, singers, and renowned film directors

such as Park Chan-Wook and Bong Joon-Ho. / ⓒ Channel A screen capture

The

cultural and artistic blacklist of 82 individuals under the Lee Myung-Bak administration.

The list includes prominent novelists, singers, and renowned film directors

such as Park Chan-Wook and Bong Joon-Ho. / ⓒ Channel A screen captureUnder Park’s regime,

approximately 9,400 individuals and 340 organizations were systematically

excluded from funding and opportunities.

Prominent figures like Nobel

Prize-winning novelist Han Kang, along with filmmakers Bong Joon-Ho and Park

Chan-Wook, found themselves blacklisted. This blatant suppression of artistic

freedom was later ruled unconstitutional, leading to legal repercussions for

key officials involved.

(Left) Former Presidential

Chief of Staff Kim Ki-Choon and (Right) Former Minister of Culture, Sports and

Tourism Cho Yoon-Sun leaving the Seoul High Court on January 24, 2024, after

being sentenced to two years and one year and two months in prison, respectively,

during the retrial of the "Cultural Blacklist" case under the Park

Geun-Hye administration. ⓒNews1

(Left) Former Presidential

Chief of Staff Kim Ki-Choon and (Right) Former Minister of Culture, Sports and

Tourism Cho Yoon-Sun leaving the Seoul High Court on January 24, 2024, after

being sentenced to two years and one year and two months in prison, respectively,

during the retrial of the "Cultural Blacklist" case under the Park

Geun-Hye administration. ⓒNews1This warns that political

power can suppress art even in modern society, and suggests that the cultural

and artistic community must continuously protect freedom of expression.

Conclusion

Art possesses the profound power to speak truth even under oppression. Han Kang, in her Nobel Prize acceptance speech, declared, “Art is the most potent tool for preserving human dignity and freedom.” This sentiment underscores the responsibility of artists to safeguard the liberty of expression.

Nobel Prize Acceptance Lecture ⓒnobelprize.org

The failure of the “Yoon

Suk-Yeol Insurrection” is not merely an end but a new beginning—an opportunity

for Korea’s art world to amplify its authentic voice. Art remains the most

formidable beacon for truth and freedom, a reminder that beauty and brutality

coexist to challenge and inspire us.

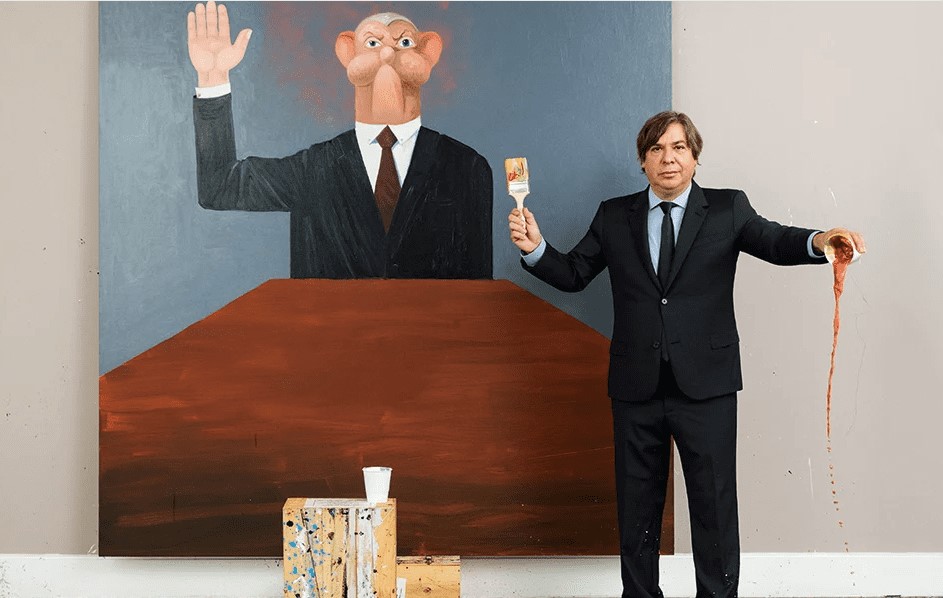

Jay Jongho Kim graduated from the Department of Art Theory at Hongik University and earned his master's degree in Art Planning from the same university. From 1996 to 2006, he worked as a curator at Gallery Seomi, planning director at CAIS Gallery, head of the curatorial research team at Art Center Nabi, director at Gallery Hyundai, and curator at Gana New York. From 2008 to 2017, he served as the executive director of Doosan Gallery Seoul & New York and Doosan Residency New York, introducing Korean contemporary artists to the local scene in New York. After returning to Korea in 2017, he worked as an art consultant, conducting art education, collection consulting, and various art projects. In 2021, he founded A Project Company and is currently running the platforms K-ARTNOW.COM and K-ARTIST.COM, which aim to promote Korean contemporary art on the global stage.