In this evolving environment, the Korean art market experienced its second golden era, transitioning from the late 1980s to the early 1990s. As the nation underwent a pronounced economic expansion and greater integration into the global sphere, the art scene also thrived.

Image by Susan Q Yin on Unsplash

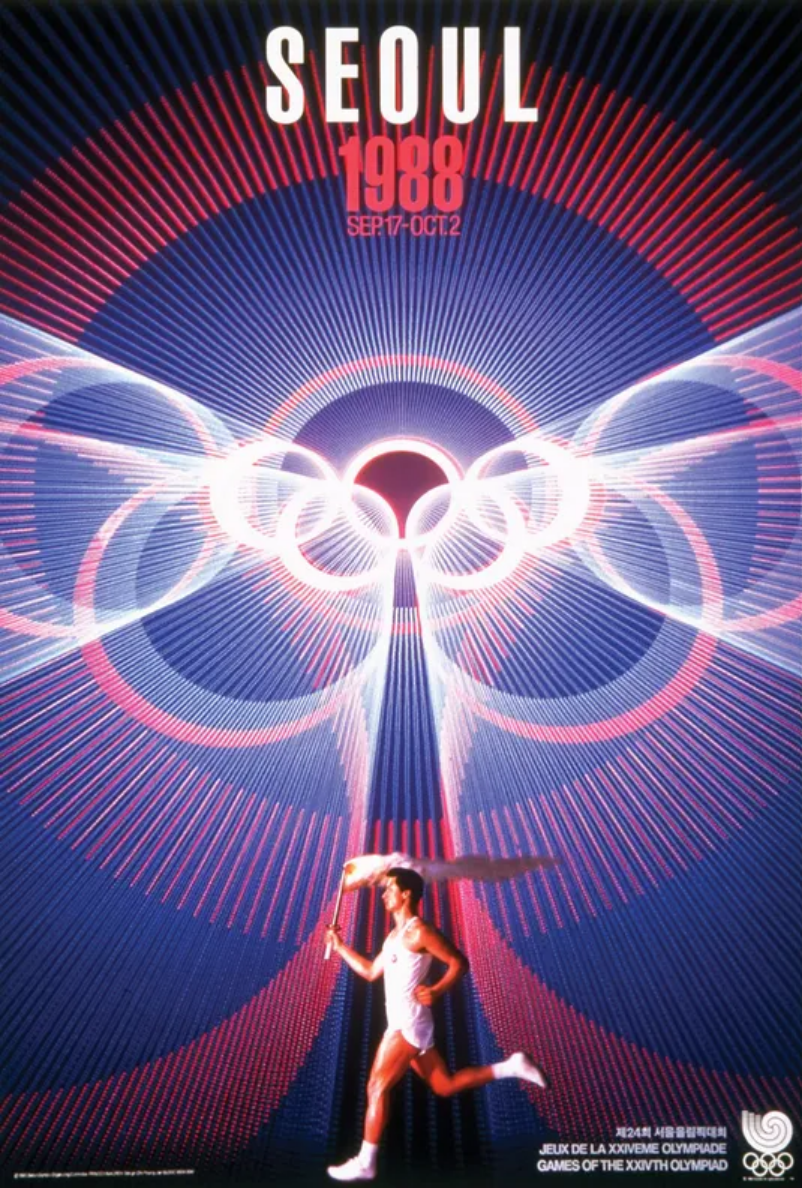

Image by Susan Q Yin on UnsplashIn the latter part of the 1980s, South Korea underwent a significant transformation. The hosting of the 1988 Seoul Olympics, symbolizing the nation’s resurgence and the end of the Cold War, marked a pivotal moment for the country’s economy, which experienced rapid growth.

The year before, in 1987, South Korea witnessed the June Uprising, an anti-government protest against the military junta. Following this, a restructured democratic constitution led the South Korean government to introduce several laws and set up institutions to encourage globalization.

In this evolving environment, the Korean art market experienced its second golden era, transitioning from the late 1980s to the early 1990s. As the nation underwent a pronounced economic expansion and greater integration into the global sphere, the art scene also thrived.

Poster of the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games. Design by Cho Yong-je of Seoul National University.

In 1989, South Korea entirely liberalized international travel and commenced the import of foreign goods. Initially, in the case of artworks, this liberalization was restricted to select items, primarily paintings. However, by 1992, the regulations were broadened to encompass all art forms. This not only introduced international art to South Korea but also provided a gateway for local artists to showcase their work globally.

The wave of globalization significantly influenced South Korean policies, leading the government to take compulsory steps to promote cultural development and creativity. In 1990, the government divided the Ministry of Culture and Public Communication into two distinct segments: the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Public Communication. This restructuring was followed by the Museum and Fine Arts Promotion Act in late 1991, which sparked the founding of many museums commencing in 1992. With more museums came more artists, broadening the art audience.

Furthermore, the Artwork Decoration Act enacted in 1984 played a role in revitalizing the sculpture market, which had been relatively marginalized. This act, originally concerning architectural artwork decoration, was expanded in 1985. By the time of the 1986 Asian Games, the act’s applicability was broadened to include diverse artistic genres such as painting, sculpture, crafts, photography, calligraphy, murals, public statues, and other symbolic structures, thereby enriching the variety of artworks in the Korean market.

Exterior view of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon Branch (MMCA Gwacheon). Courtesy of the museum.

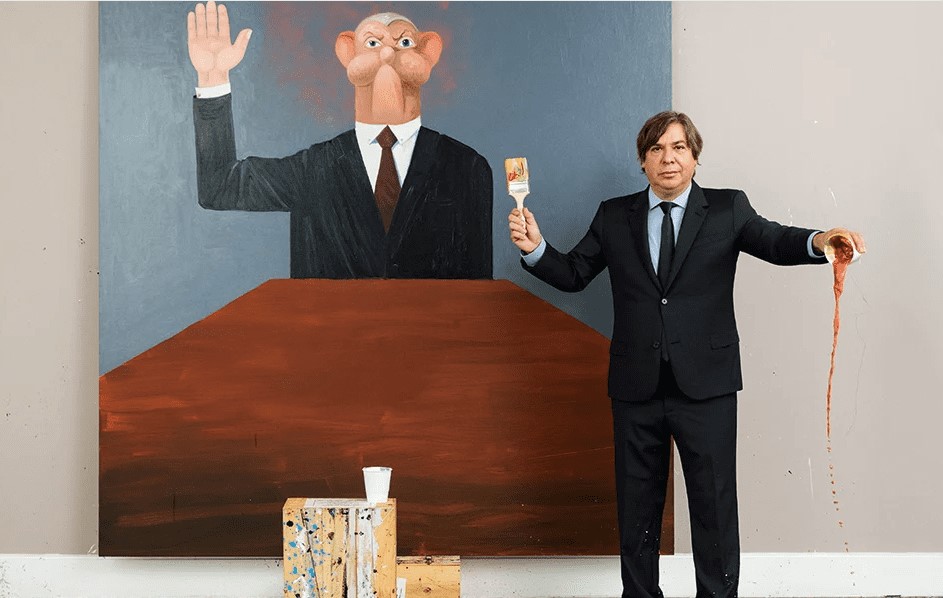

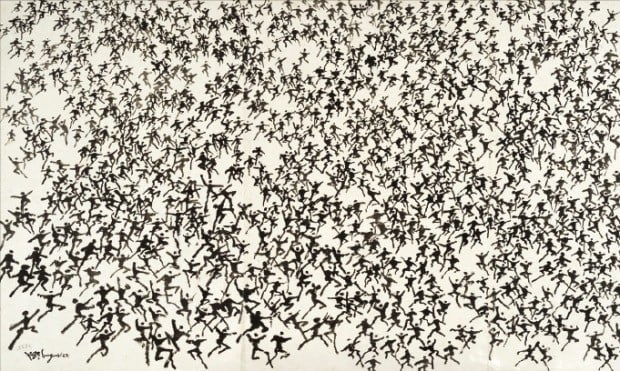

Exterior view of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Gwacheon Branch (MMCA Gwacheon). Courtesy of the museum.Amid the economic progression and heightened globalization efforts, the favored genres in the art market changed significantly. Korean traditional painting, which held dominance up until the 1970s, began witnessing a decline in the 1990s. Meanwhile, Western-style figurative painters rose in prominence, overshadowing abstract artists. Yet, within the abstract sphere, artists such as Whanki Kim, Nam Kwan, and Yoo Youngkuk were still admired. Simultaneously, artists like Suh Se-ok, Lee Ufan, and Chun Kyung-ja, who embraced more traditional styles, maintained their esteemed positions in the art world.

This transition can be attributed to the Westernization of lifestyles, where living in an apartment came to symbolize wealth. After the 1980s, as economic development expanded the middle-class population, art enthusiasts displayed a preference for Western paintings for their apartment interiors.

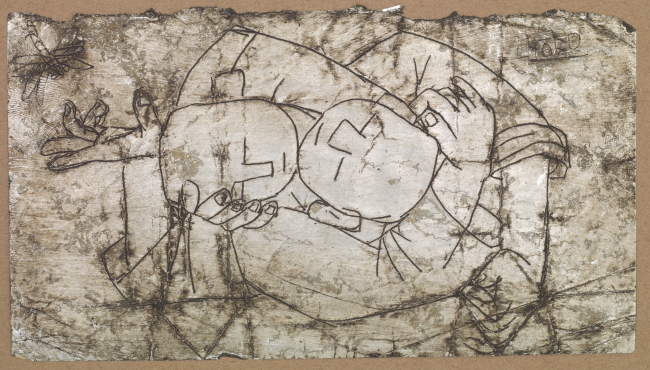

During this period, while the art market saw exponential growth, the valuation of artworks also witnessed a dramatic surge. In the early 1990s, works by prominent artists such as Lee Jung-seob and Park Soo-keun fetched approximately 100 million KRW at auctions, a sum comparable to the cost of an apartment at that time. This era’s art market was predominantly shaped by Western-style paintings by experienced and mid-career artists.

Lee Ungno, ‘People,’ 1986, Ink on Korean paper, 167 x 266 cm, Collection of Lee Ungno Museum.

Toward the end of the 1980s, the art scene witnessed the emergence of art fairs. In 1986, the Galleries Association of Korea inaugurated the Hwarang Art Fair (Hwarang Misulje), drawing participation from approximately 37 galleries. Notably, the initial editions of this fair took place at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Deoksugung) and the Hoam Gallery, bearing a closer resemblance to art festivals than commercial marketplaces.

Korean art galleries also began making their mark on the international stage during this period. In 1985, the Gana Art Center became the first Korean gallery to participate in the FIAC (Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporain) held in France. The Hyundai Gallery, in 1987, became one of the first Korean galleries to participate in the Chicago International Art Exposition.

However, 1990 brought with it regulatory challenges. The income tax law underwent a revision to deter real estate speculation, and this amended law also encompassed art and antiques. Despite its actual implementation being delayed until 2013, the ripple effect of the 1990 law was enough to cause the art market to shrink while art infrastructure was still lacking. The number of popular artists also decreased, reaching only about one-third of its peak during the art market surge of the late 1980s.

Lee Jung Seob, 'Two Children,' (1950s). Courtesy of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul.

At that time, the Korean art market had expanded considerably, yet it struggled to keep up with the structure of international art markets. Art fairs were predominantly hosted in public museums and corporate art galleries, indicating that the scene had yet to achieve full independence. Additionally, the auction system, essential for a thriving art market, had not been firmly established until the 1990s. The art community grappled with a shortage of experienced curators, and renowned public art institutions were scarce. As a result, the criteria for art evaluation remained underdeveloped.

Adding to the complexity, the art pricing system, with roots in practices from the late 1970s, persisted in its ambiguity. Artworks were priced according to their size and the popularity of the artist rather than their artistic merit, and a dual pricing model was still in place, leading to discrepancies between gallery list prices and final sale values.