Recently, the Korean art scene has been embroiled in a heated debate over the potential establishment of a branch of the iconic Centre National d'Art et de Culture Georges-Pompidou (Pompidou Center) in Korea. This article examines the key arguments for and against this initiative, exploring the underlying issues and potential outcomes.

Pompidou Center’s Characteristics

The Pompidou Center is a world-renowned cultural landmark in Paris, designed by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers in 1977. It stands out for its radical architectural design, with structural elements like pipes and support beams exposed on the outside of the building. Over the years, it has become a beloved destination for art enthusiasts worldwide.

Ponpidou

Center from home page ©Julien Fromentin

Ponpidou

Center from home page ©Julien FromentinThe Push for Overseas Branches

The

backdrop to this debate stems from the Pompidou Center's upcoming renovation.

The center is scheduled to undergo significant repairs from 2025 until 2030,

with an estimated cost of €260 million (about 370 billion KRW).

During this

time, it plans to expand its exhibition space by reusing previously unused

areas. Most of the renovation costs will be covered by the French government,

but the center is also seeking additional funding by leasing its collection

abroad or hosting long-term exhibitions at foreign branches.

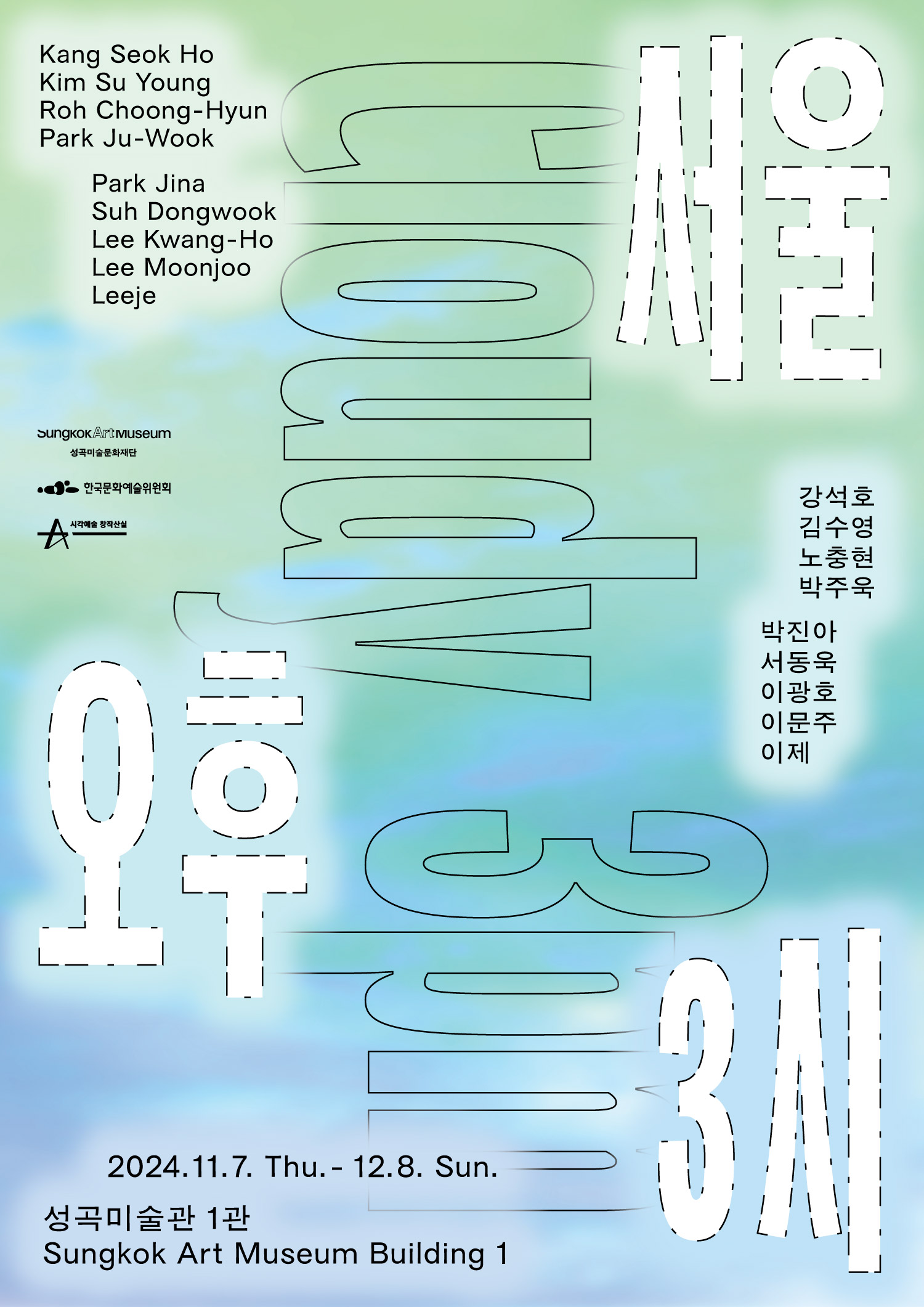

2025-2030

Pompidou Center Branch or Exhibition Attraction Plan from Ponpidou Home Page

2025-2030

Pompidou Center Branch or Exhibition Attraction Plan from Ponpidou Home PageAlready, some locations have secured exhibitions or are negotiating branch establishments. However, not all efforts have been successful—plans to establish a branch in New Jersey, USA, recently fell through due to concerns over the high operating costs that would have been funded by taxpayers.

Hanwha’s Pompidou Branch in Seoul

In

2023, Hanwha Group finalized a MOU with the Pompidou Center ©Hanhwa

In

2023, Hanwha Group finalized a MOU with the Pompidou Center ©HanhwaIn 2023, Hanwha Group finalized a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Pompidou Center, securing plans to open a branch in Seoul’s 63 Building by 2025.

Hanhwa

63 Building (Photo:Shutterstock)

Hanhwa

63 Building (Photo:Shutterstock)The

group has already begun converting the space, formerly home to an aquarium,

into a 1,000-pyeong (approx. 3,300 square meters) art museum. Notably, renowned

architect Jean-Michel Wilmotte, who has worked on the Louvre and the British

Museum, will lead the redesign efforts.

Hanwha

has secured the operating rights for four years and plans to hold two major

exhibitions annually, featuring masterpieces by Matisse, Picasso, Chagall, and

other 20th and 21st-century artists. Through this partnership, Hanwha aims to

foster international art exchanges and elevate Korea’s presence on the global

art stage. The branch is expected to contribute significantly to making Seoul a

global art hub, with the added benefit of boosting art tourism and the local

economy.

Busan’s Competing Pompidou Branch Plan

2022 Busan Mayor Park

Heong-joon visits Pompidou Center ©Busan

2022 Busan Mayor Park

Heong-joon visits Pompidou Center ©BusanMeanwhile, Busan has announced plans to open a Pompidou Center branch by 2031 at Igidae International Art Center. This ambitious project aims to transform Igidae, a coastal region known for its scenic beauty, into a large-scale art park.

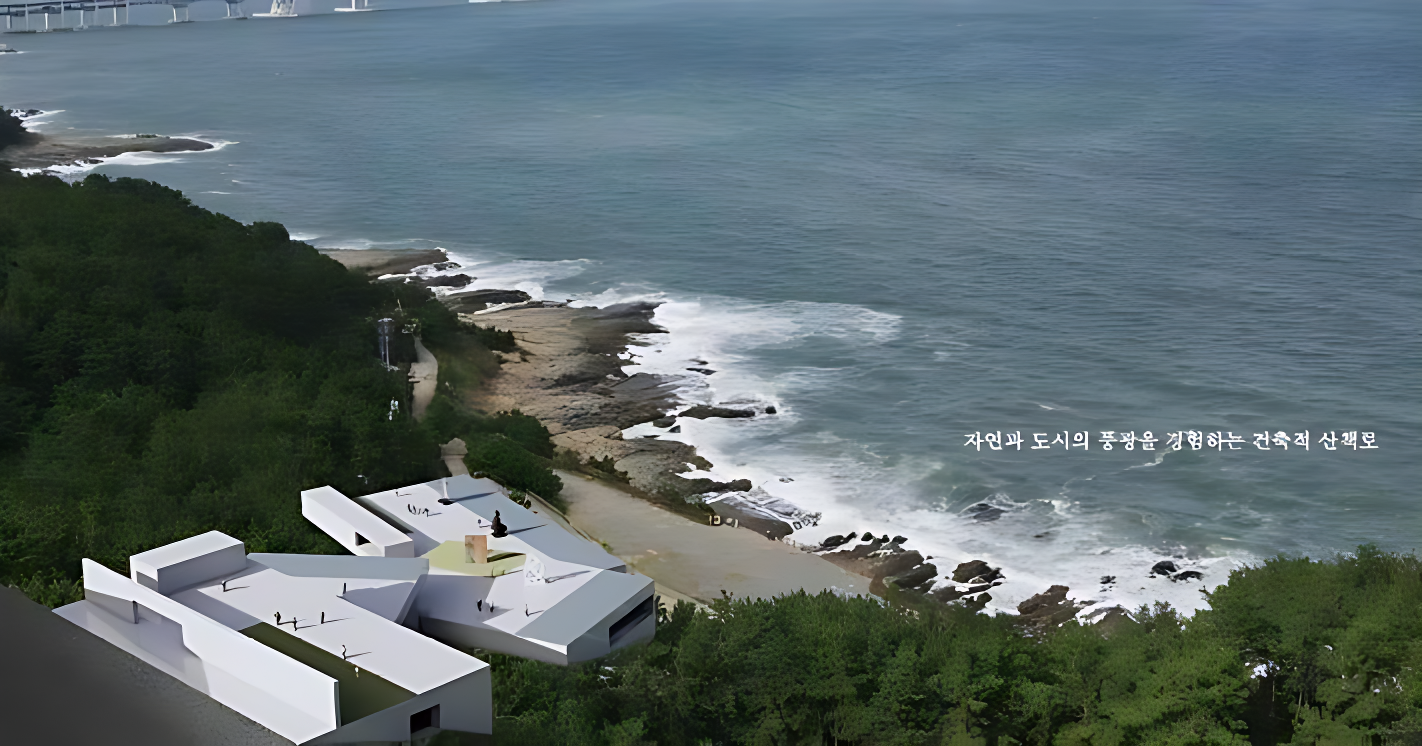

Aerial view of 'Pompidou

Center Busan,' a branch of the world-class art museum to be built in the Igidae

Art Park in Nam-gu, Busan (Photo:Busan)

Aerial view of 'Pompidou

Center Busan,' a branch of the world-class art museum to be built in the Igidae

Art Park in Nam-gu, Busan (Photo:Busan)The proposed museum will cover 15,000 square meters and include exhibition halls, creative studios, performance spaces, and educational facilities. The total project cost is estimated at 108.1 billion KRW, with annual operating costs of 12.5 billion KRW. The museum is projected to attract around 460,000 visitors in its first year of operation.

Aerial

view of Igidae International Art Center (Photo:Busan)

Aerial

view of Igidae International Art Center (Photo:Busan)Incheon International Airport Corporation's bid for the Pompidou Center falls through

Incheon International Airport was in talks with the Pompidou Center as far back as 2022, but the astronomical cost of the project led to the cancellation. Instead, the airport is now looking into the possibility of hosting various international art museums, most notably the Louvre, as it aims to develop into a 'cultural art airport'.

The Debate: Pros and Cons of the Busan Branch

On

the 11th, tourism-related associations in favor of the Pompidou Center Busan

Branch are holding a press conference at the Busan City Council. ©Yonhap

On

the 11th, tourism-related associations in favor of the Pompidou Center Busan

Branch are holding a press conference at the Busan City Council. ©YonhapSupporters argue that the branch will be a key driver in establishing Busan as a global cultural tourism hub. They anticipate the branch will attract significant economic benefits, with Busan city officials estimating an economic ripple effect of about 448.3 billion KRW. The branch is seen as a critical asset for boosting the city’s profile on the global art map and fostering international cultural exchanges.

Local cultural and artistic

organizations opposing the Pompidou Center's Busan branch hold a press

conference on Nov. 11.

Local cultural and artistic

organizations opposing the Pompidou Center's Busan branch hold a press

conference on Nov. 11.Courtesy of the Busan Civil Society Task Force Against the Pompidou Center's Busan Branch

Opponents, however, focus on the financial burden. They highlight the high construction and maintenance costs, with concerns over how the city will fund the 1,100 billion KRW construction budget and the annual operating expenses of over 12 billion KRW. Critics also fear that this project might hinder the local art scene’s organic growth, as resources may be diverted away from nurturing homegrown talent. Additionally, there are concerns that the city has pushed the project forward without sufficient public debate, leading to accusations of a rushed and top-down approach.

Learning from the Bilbao Guggenheim

A common reference point in this debate is the success of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, which is often cited as a model for how an iconic art museum can revitalize a city. However, the Guggenheim’s success was not merely the result of a spectacular building or exhibitions but a culmination of years of strategic planning and cooperation.

Bilbao Guggenheim, Spain

Key factors in Bilbao’s success include:

Political Collaboration: The project required close cooperation between Spain’s central government, the Basque regional government, and the city of Bilbao. The Basque government, in particular, invested over $100 million to support the museum, and without this political and financial backing, the project would not have been possible.

Community Engagement: Initial resistance from the local community was overcome through extensive dialogue and public relations efforts. Project leaders worked to demonstrate how the museum would provide long-term benefits to the local economy and quality of life, ultimately securing public support.

Urban Regeneration: The Guggenheim was part of a broader, long-term urban regeneration strategy. Over two decades, Bilbao underwent significant infrastructure improvements, including port redevelopment, environmental clean-up, and transportation upgrades, which helped transform the city into a cultural and economic hub.

Close

Collaboration with the Guggenheim Foundation: The Guggenheim Foundation

played a vital role in the museum’s operations and programming, providing

curatorial guidance, marketing strategies, and operational expertise. This

long-term collaboration was essential for the museum’s success.

These

lessons show that building an iconic museum requires far more than just a

beautiful building or famous art. It demands comprehensive urban planning,

political cooperation, and sustained community involvement.

Conclusion

Art is

fundamentally a product of the spirit, and simply importing famous works from

abroad does not guarantee sustained success or tourist appeal. Establishing an

art museum, particularly one associated with a prestigious global institution,

is not as straightforward as selling luxury goods like Hermès or Louis Vuitton.

It requires meticulous planning, substantial budgets, and long-term

collaboration between local governments and citizens. Even after years of

investment and effort, the results may still be uncertain.

Korea,

both in Seoul and its other cities, seems to approach cultural and artistic

development with a focus on outward appearances rather than a genuine

commitment to long-term growth. Many cities already have large art centers and

museums, yet they struggle to make full use of these resources. Before pursuing

yet another high-profile project, cities like Busan may benefit from focusing

on maximizing their existing infrastructure and building trust and

collaboration with local communities. Only through careful deliberation and

long-term vision can such projects truly succeed.

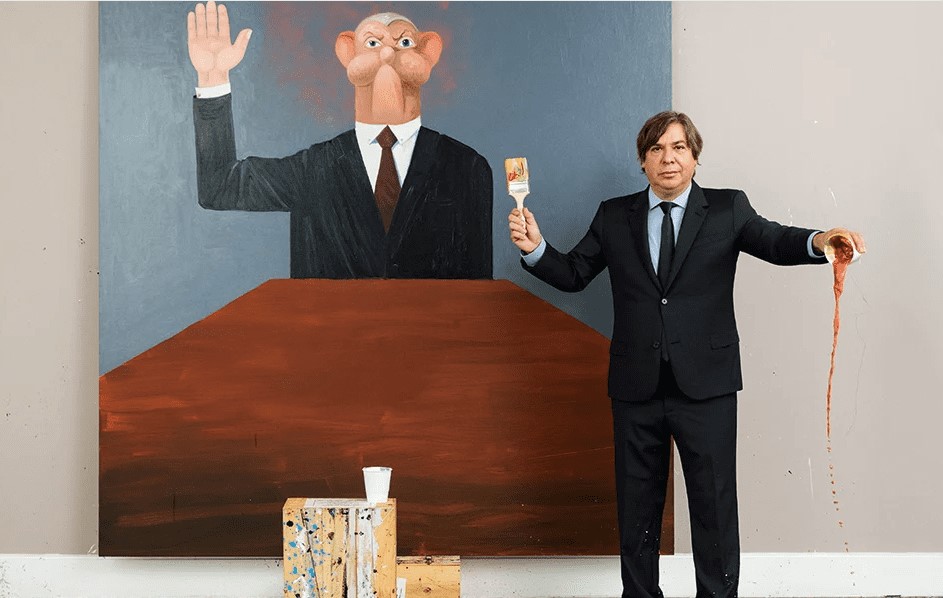

Jay Jongho Kim graduated from the Department of Art Theory at Hongik University and earned his master's degree in Art Planning from the same university. From 1996 to 2006, he worked as a curator at Gallery Seomi, planning director at CAIS Gallery, head of the curatorial research team at Art Center Nabi, director at Gallery Hyundai, and curator at Gana New York. From 2008 to 2017, he served as the executive director of Doosan Gallery Seoul & New York and Doosan Residency New York, introducing Korean contemporary artists to the local scene in New York. After returning to Korea in 2017, he worked as an art consultant, conducting art education, collection consulting, and various art projects. In 2021, he founded A Project Company and is currently running the platforms K-ARTNOW.COM and K-ARTIST.COM, which aim to promote Korean contemporary art on the global stage.