Korean-Colombian artist Gala Porras-Kim (b. 1984) has been interested in how traces of past civilizations are defined and reinterpreted within contemporary contexts. Her work examines the multilayered narratives of both tangible relics housed in institutional spaces such as museums and galleries and intangible heritage like sound, language, and history.

Gala Porras-Kim, Whistling

and Language Transfiguration, 2012 ©Commonwealth and Council

Gala Porras-Kim, Whistling

and Language Transfiguration, 2012 ©Commonwealth and CouncilGala Porras-Kim’s early work, Whistling

and Language Transfiguration (2012), involves a sound piece produced

as a vinyl record that translates the tonal Zapotec language, spoken by the

Zapotec Indigenous people of Mexico, into whistles. The Zapotec language, used

as a strategy of resistance against Spanish colonizers since the 16th century,

mimicked words through tonal whistling, disguising conversations as music.

Porras-Kim imitated and recorded the

endangered Zapotec language, which has survived solely through oral

transmission, using her own whistling and further encoded the sounds as musical

notation. Her exploration of a vanishing language questions how we can approach

unreadable or inaccessible languages—information that eludes our full

understanding.

Gala

Porras-Kim, Muscle Memory, 2017 ©Gala Porras-Kim

Gala

Porras-Kim, Muscle Memory, 2017 ©Gala Porras-KimCreated

in 2017, Muscle Memory (2017) is a video work that records

the silhouette of a dancer attempting Korean traditional dance without access

to definitive documentation. Traditional dances, transmitted through bodily

practices rather than written records, inherently carry an ontological

vulnerability, as they are nearly impossible to preserve and pass down in a

perfectly identical state.

The

dancer's movements, shaped by their unique physique, anatomical structure, and

interpretation of choreography, become a vessel for preserving and containing

individualized knowledge through muscle memory. The video, focusing solely on

the dancer's silhouette, highlights the body and muscles as vessels that

encapsulate the intangible cultural heritage of dance.

These

works aim to document intangible cultural legacies handed down through

collective history, translating them into the artist's unique visual language

and resisting frameworks rooted in Western modernity.

Gala

Porras-Kim, Proposal For The Reconstituting Of Ritual Elements For The

Sun Pyramid At Teotihuacan, 2019 ©Gala Porras-Kim

Gala

Porras-Kim, Proposal For The Reconstituting Of Ritual Elements For The

Sun Pyramid At Teotihuacan, 2019 ©Gala Porras-KimGala Porras-Kim has also shown a deep

interest in artifacts unearthed from ancient sites such as the Mayan

civilization, Egypt, and dolmens, which lose their original context when

excavated and relocated to museums for display or preservation. Artifacts forcibly

displaced under the pretext of research and conservation often find themselves

encased in the artificially frozen time of museum glass cases or stripped of

their status as artifacts altogether.

The artist examines the complex lives of

these objects, which have lost their original functions and places, and

questions the institutional practices and policies shaped under the pretext of

preserving culture and history. In doing so, Porras-Kim engages in concrete

practices by collaborating directly with holding institutions or research

centers to explore the regulations and laws surrounding these artifacts.

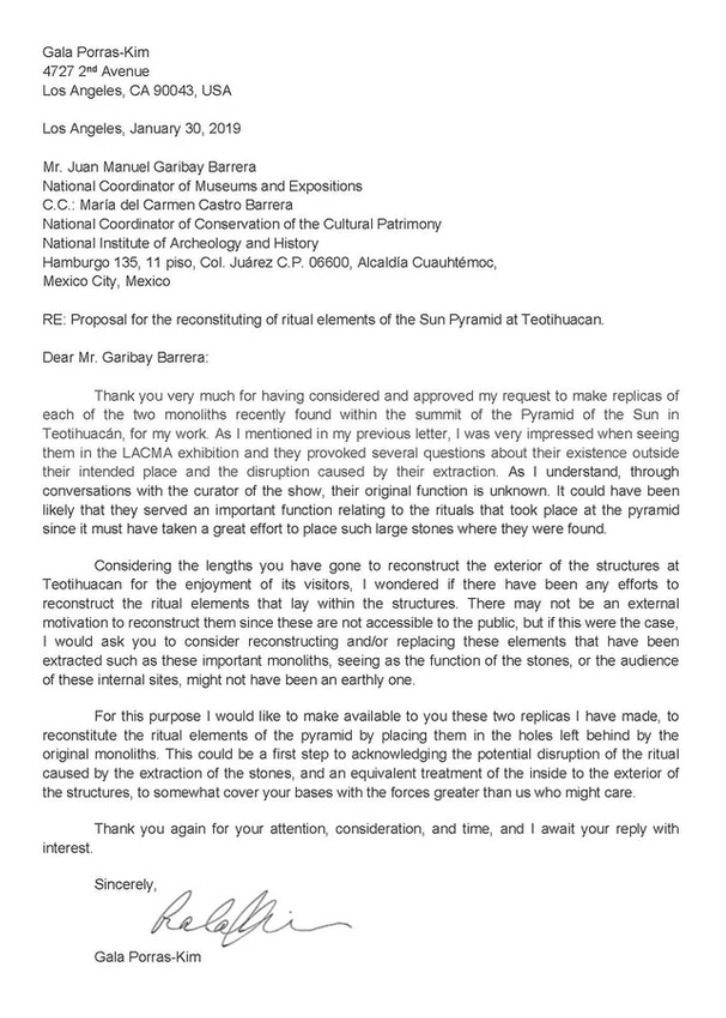

For instance, her 2019 work,

Proposal for the Reconstituting of Ritual Elements for the Sun Pyramid

at Teotihuacan, exemplifies a multidisciplinary artistic approach to

two massive stones that once stood atop the Sun Pyramid at the archaeological

site of Teotihuacan, Mexico.

Gala

Porras-Kim, Proposal For The Reconstituting Of Ritual Elements For The

Sun Pyramid At Teotihuacan, 2019 ©Gala Porras-Kim

Gala

Porras-Kim, Proposal For The Reconstituting Of Ritual Elements For The

Sun Pyramid At Teotihuacan, 2019 ©Gala Porras-KimThe

two massive stones, presumed to have been used for ritualistic purposes, are

now housed in a museum, leaving only two empty pits at the top of the pyramid

where they once stood. With permission from the research institute, Porras-Kim

created replicas of the stones and submitted a formal proposal to the

institute. In her proposal, the artist emphasized the need to revive the

ritualistic significance embedded in these structures and suggested placing her

replicas at the original locations of the stones atop the pyramid.

Accompanying

this project is the monochromatic painting Two Plain Stelas in the

Looter Pit at the Top of the Sun Pyramid at Teotihuacan (2019), a

black graphite rendering of the dark night sky as seen from within the Sun

Pyramid. Through repeated, meticulous pencil strokes, the work poetically

evokes the cosmological significance of the Sun Pyramid, a sacred site for the

Teotihuacanos who worshipped the sun deity.

Gala Porras-Kim, Precipitation

for an arid landscape, 2021-ongoing ©Gala Porras-Kim

Gala Porras-Kim, Precipitation

for an arid landscape, 2021-ongoing ©Gala Porras-KimPorras-Kim extends her practice beyond

reviving the inherent meaning of artifacts to restoring their spiritual life

and reawakening their suppressed magical powers and abilities. She creatively

reconstructs the contexts surrounding artifacts that modern scientific

technologies, grounded in Western epistemology, often dismiss as superstition

or primitivism.

For instance, Precipitation for an

arid landscape (2021–ongoing) invokes the sacred history of the

cenote caves at Chichén Itzá, located in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. These

mystical natural formations were regarded by the Maya as portals connecting the

earthly and underworld realms and as sacred sites where the rain god Chaac

resided.

In the early 20th century, artifacts from

these cenotes, totaling approximately 30,000 pieces, including relics and human

remains, were relocated to Harvard University’s Peabody Museum. Separated from

Chaac and removed from their original environment, these artifacts now reside

in a dry setting, devoid of the rainwater that once imbued them with spiritual

significance.

Gala Porras-Kim, Precipitation

for an arid landscape, 2021-ongoing, Installation view at Fowler

Museum ©Fowler Museum. Photo: Elon Schoenholz.

Gala Porras-Kim, Precipitation

for an arid landscape, 2021-ongoing, Installation view at Fowler

Museum ©Fowler Museum. Photo: Elon Schoenholz.Porras-Kim

sent a letter to the director of the Peabody Museum proposing that fragments

detached from the artifacts be reunited with rainwater, replicating their

original environment. To realize this idea, she collected dust from the cenote

artifacts stored in the museum's archives and combined it with resin extracted

from copal trees, a tropical plant native to Central America, to create a new

object.

In

collaboration with exhibition institutions, Porras-Kim orchestrates a daily

ritual where water is sprinkled on the object, symbolically reuniting it with

rainwater. Through this ritual, the object serves as a ceremonial intermediary,

reconnecting the artifacts, human remains, and the Maya civilization’s rain

god, Chaac.

Gala Porras-Kim, A

terminal escape from the place that binds us, 2021 ©Gala Porras-Kim

Gala Porras-Kim, A

terminal escape from the place that binds us, 2021 ©Gala Porras-KimMeanwhile, A terminal escape from

the place that binds us (2020–ongoing), presented at the 13th Gwangju

Biennale, is a painting project aimed at summoning the spirits of remains

displayed in museums. In 2019, Porras-Kim visited Gwangju and reflected on the

institutionalized afterlife imposed upon the human remains exhibited in the

National Museum of Gwangju, a fate they never chose for themselves.

Through the practice of necromancy,

divination with ink stains, Porras-Kim sought to summon these spirits and asked

them to reveal their desired final resting places. Using the marbling

technique, where paint floats on the surface of water, she engaged with the

spirits to manifest images symbolizing the ideal locations where they wish

their remains to rest.

Gala

Porras-Kim, Out of an instance of expiration comes a perennial showing,

2022, Installation view of “Korea Artist Prize 2023” (MMCA, 2023) ©MMCA

Gala

Porras-Kim, Out of an instance of expiration comes a perennial showing,

2022, Installation view of “Korea Artist Prize 2023” (MMCA, 2023) ©MMCAIn

her 2022 work Out of an instance of expiration comes a perennial showing,

Porras-Kim collected mold spores from the British Museum's storage facilities

and cultivated them on muslin cloth soaked in bacterial growth medium, encased

within acrylic display boxes. Over the course of the exhibition, the mold

spores began to proliferate, gradually filling the previously blank fabric and

transforming into a vibrant, living micro-landscape.

Typically,

mold spores are considered indicators of an artifact's preservation status and

are classified as part of the collection, remaining confined within storage. By

collecting and nurturing these spores, Porras-Kim liberated them from the

confines of the repository, allowing them to grow and transform into a new form.

Gala

Porras-Kim, The weight of a patina of time, 2023,

Installation view of “Korea Artist Prize 2023” (MMCA, 2023) ©MMCA

Gala

Porras-Kim, The weight of a patina of time, 2023,

Installation view of “Korea Artist Prize 2023” (MMCA, 2023) ©MMCAFor

the “Korea Artist Prize 2023” exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and

Contemporary Art Korea, Gala Porras-Kim created The weight of a patina

of time, which focuses on the dolmens located in Gochang,

Jeollabuk-do. The dolmens, which functioned as ritual markers for burial sites

during the first millennium BCE, have gradually lost their significance and

function over time, only to be rediscovered and designated as a UNESCO World

Heritage site in the 2000s.

Originally

simple natural stones, the dolmens transformed into burial monuments, became

makeshift drying racks for laundry and chili peppers, and now are protected as

cultural heritage sites. Porras-Kim pays attention to the changing roles of

these structures over time, expressing three perspectives on the dolmens

through three large-scale drawings.

In

one drawing, the black graphite layers depict a landscape from the perspective

of the deceased buried beneath the dolmen. Another drawing, resembling a

photograph, represents the present-day situation where the dolmen is a

designated cultural heritage site. The third abstract drawing imagines the view

from the moss that has existed at the site for thousands of years,

incorporating the perspectives of insects and animals. Displayed side by side,

the three drawings present the dolmen's multifaceted reality, encompassing

various temporal, spatial, and experiential dimensions.

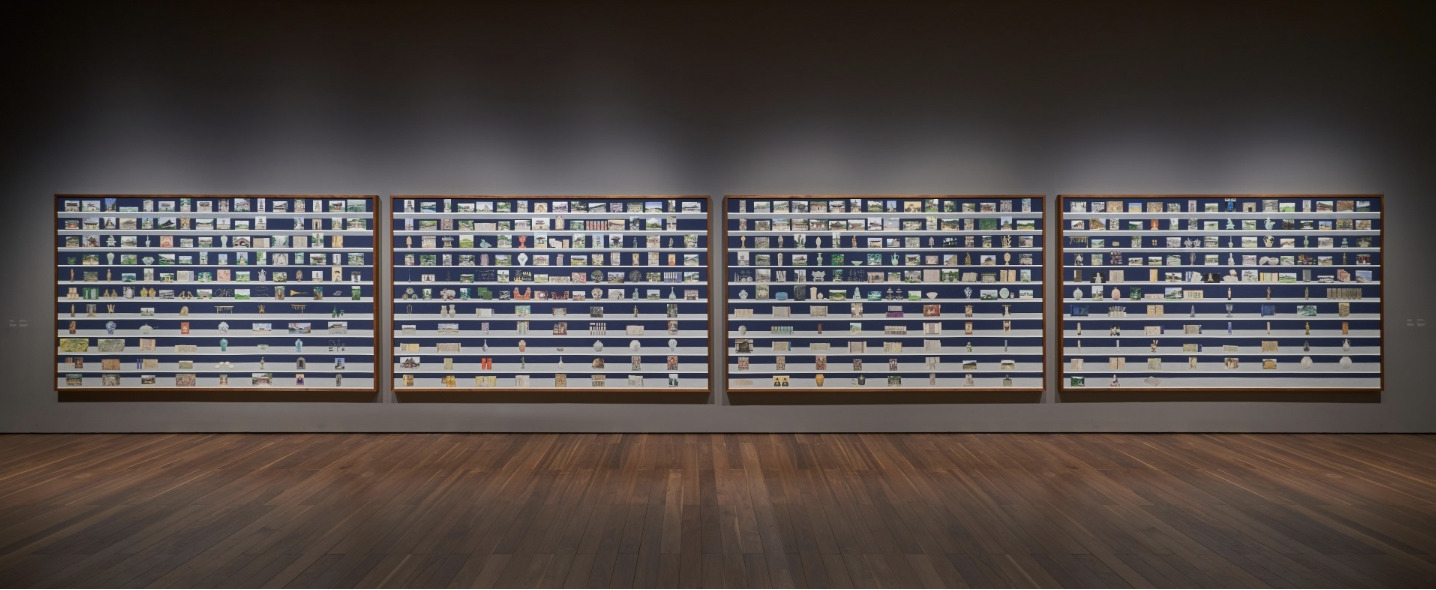

Gala Porras-Kim, 530

National Treasures, 2023, Installation view of “Gala Porras-Kim:

National Treasures” (Leeum Museum of Art, 2023) ©Gala Porras-Kim. Photo: Yang

Ian

Gala Porras-Kim, 530

National Treasures, 2023, Installation view of “Gala Porras-Kim:

National Treasures” (Leeum Museum of Art, 2023) ©Gala Porras-Kim. Photo: Yang

IanIn

2023, Gala Porras-Kim created 530 National Treasures, a

painting that brings together the national treasures of South and North Korea.

The treasures are depicted in alternating order from the top left, according to

their national treasure numbers. The sparse bottom portion of the painting

reflects the fact that North Korea has fewer national treasures compared to

South Korea.

The

origins of these national treasures trace back to a list of treasures

designated by Japan in 1933 during the colonial period. Therefore, most of the

artifacts in the painting were originally unified as cultural heritage under

the name of Joseon before the division of Korea. However, after the liberation

and subsequent division of the peninsula, the list was split, and South and

North Korea each began managing their own cultural heritage.

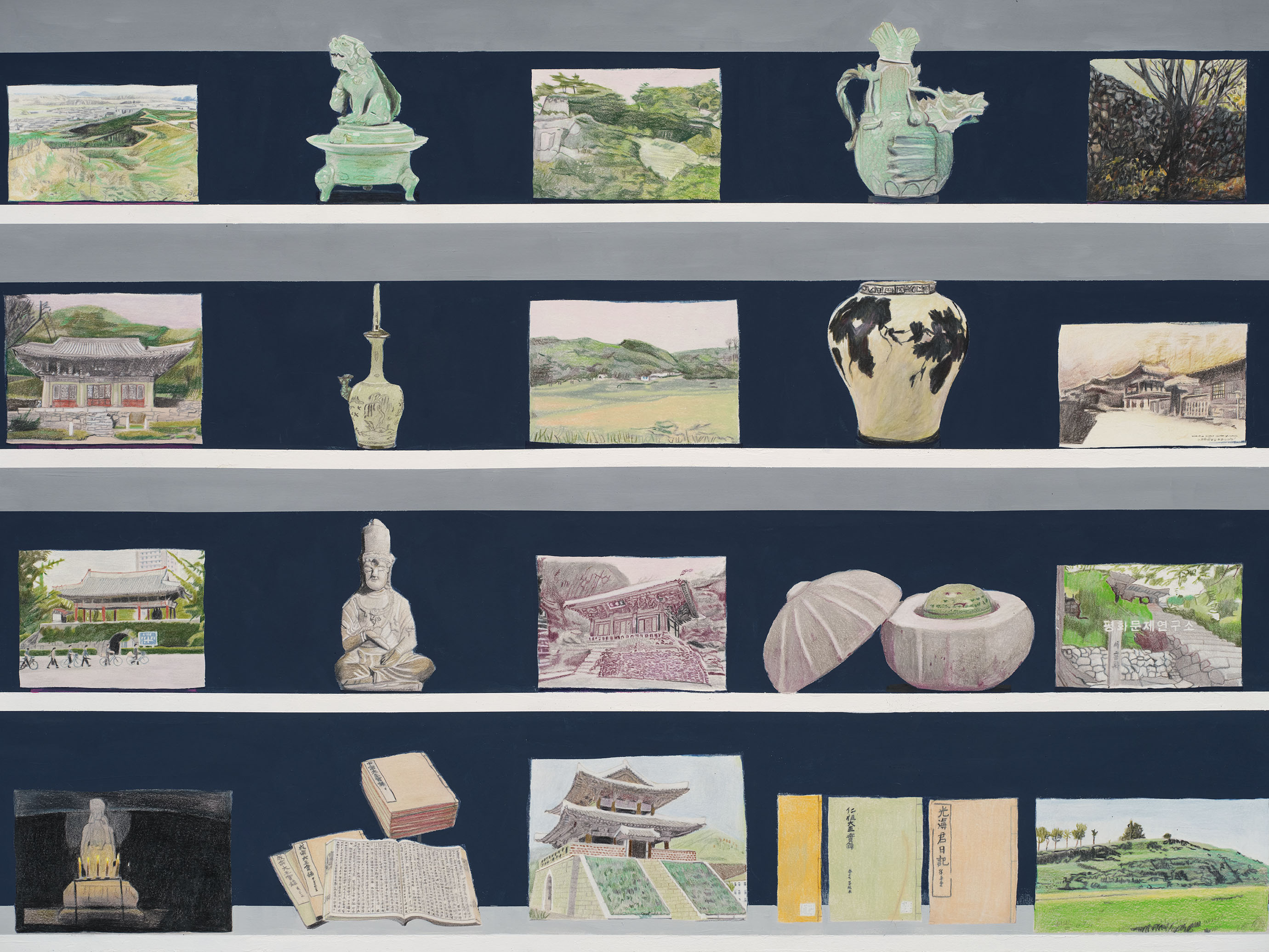

Gala Porras-Kim, 530

National Treasures (detail), 2023 ©Gala Porras-Kim

Gala Porras-Kim, 530

National Treasures (detail), 2023 ©Gala Porras-KimBy

reuniting these divided treasures in her work, the artist highlights how

colonialism and the ideology of division have shaped the management and

separation of cultural heritage. Moreover, Porras-Kim uses the empty space at

the top of the painting to reveal the existence of artifacts that were once

designated as national treasures but later de-designated for various reasons.

This invites the viewer to reflect on the criteria for designating national

treasures and questions what those criteria truly reflect.

In

this way, Gala Porras-Kim strives to reconcile the ancient desires and

traditions embedded in artifacts, which are often stored in vacuum-like

conditions in modern museums and storage rooms, with contemporary institutional

frameworks. The artist actively engages non-human entities such as objects,

human remains, dust, bacteria, and fungi, challenging the anthropocentric

attitudes of Western epistemology and colonial projects. Through this approach,

her work questions existing practices of preservation and institutions,

inviting reflection on the relationship between people and artifacts.

"In

fact, my main interest lies in understanding how the original form of

historical artifacts, which are meant to serve infinite functions, often comes

into conflict with the way they are preserved in their storage environments. I

am questioning, 'Why do methodologies intended to help us understand the past

sometimes contradict the very purpose of the objects themselves?'

I

believe that contemporary interventions, such as the storage of artifacts in

museums, tell us more about people's motivations and the relationship between

people and artifacts than they do about the past itself." (Gala

Porras-Kim, Interview for “Korea Artist Prize 2023”)

Artist Gala

Porras-Kim ©MMCA

Artist Gala

Porras-Kim ©MMCAGala

Porras-Kim lives and works in Los Angeles and London. She has had solo

exhibitions at MUAC (Mexico City), Kadist (Paris), Amant Foundation (New York,

USA), Gasworks (London), and CAMSTL (St. Louis, USA) and has been included in

the Whitney Biennial and Ural Industrial Biennial (2019), and Gwangju Biennial and

Sao Paulo Biennales (2021) Jeju Biennial and Liverpool Biennial (2022-2023).

She

was a Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard

University (2019) and the artist-in-residence at the Getty Research Institute

(2020-2022), and she is a Senior Critic at Yale sculpture department.

References

- 갈라 포라스-김, Gala Porras-Kim (Artist Website)

- 올해의 작가상 2023, 만물: 갈라 포라스-김의 작업에 대하여 - 시아오유 웡 (Korea Artist Prize 2023, The Ten Thousand Things: on the Practice of Gala Porras-Kim - Xiaoyu Weng)

- 월간미술, 갈라 포라스-김: 다중적 시선 - 임수영

- 제13회 광주비엔날레, 갈라 포라스-김 - 우리를 구속하는 장소로부터의 영원한 도피 (13th Gwangju Biennale, Gala Porras-Kim - A terminal escape from the place that binds us)

- 국립현대미술관, 올해의 작가상 2023 (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea (MMCA), Korea Artist Prize 2023)

- 리움미술관, 갈라 포라스-김: 국보 (Leeum Museum of Art, Gala Porras-Kim: National Treasures)

- 국립현대미술관, “올해의 작가상 2023” 인터뷰 2편. 갈라 포라스-김, 전소정 작가