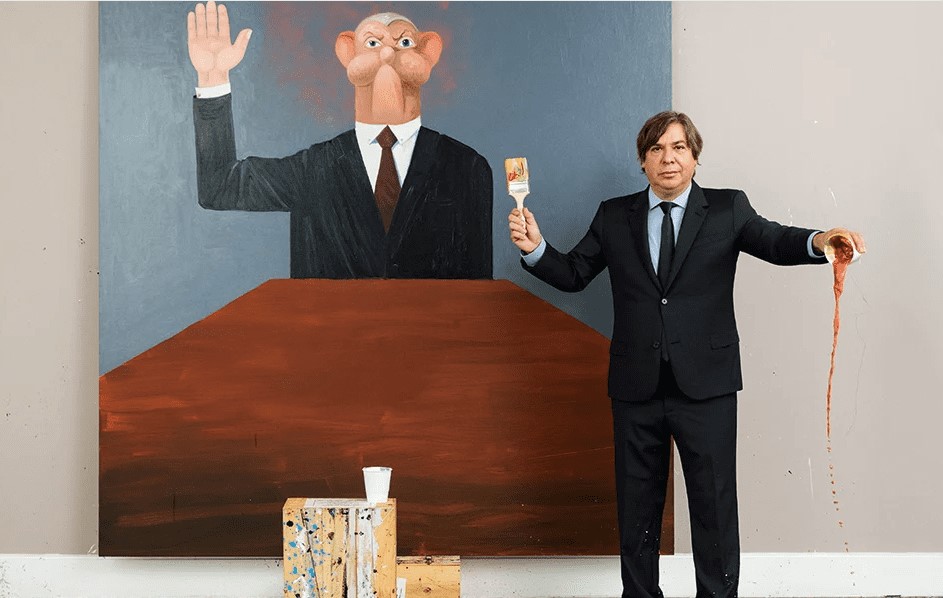

Fine Art

What

we commonly refer to as "art" (예술 in Korean)

consists of "craft" (藝) and

"technique" (術). The English word

"art" originates from the Greek word "ars," meaning

technique (techne). Before the 17th century, practical arts such as

architecture, crafts, and design were all referred to as "art."

However, as painting and sculpture separated from architecture, they came to be

called fine art.

Fine

art, as visual art, expresses the artist's thoughts and emotions through

complete forms. Unlike commercial products created to satisfy consumer demands,

fine art has a distinct production process. This difference is called

"self-purpose," which is where the purity and creativity of the

artist emerge. Importantly, self-purpose does not imply mere personal

preference or satisfaction. Instead, it gains value when the visual form

created by the artist reaches a level of universal consensus.

In

Korea, the term "art" (美術) generally refers

to "fine art" and was first used in 1911 by the Seohwa Art

Association during the Japanese colonial period. In Korea, art before 1945 is

usually called modern art, and after 1945, contemporary art. Both terms

translate to "Modern Art."

The

problem arises when we use the term "modern art" to refer to

post-1970s contemporary art. From a perspective that "language shapes

concepts," the emergence of new terminology reflects a change in meaning.

If we don’t properly grasp this change and confine it to old frameworks, it can

lead to cultural anomie, akin to putting fresh apples in a rotten box.

Therefore, I would like to clarify the meaning of contemporary art briefly.

Modern Art

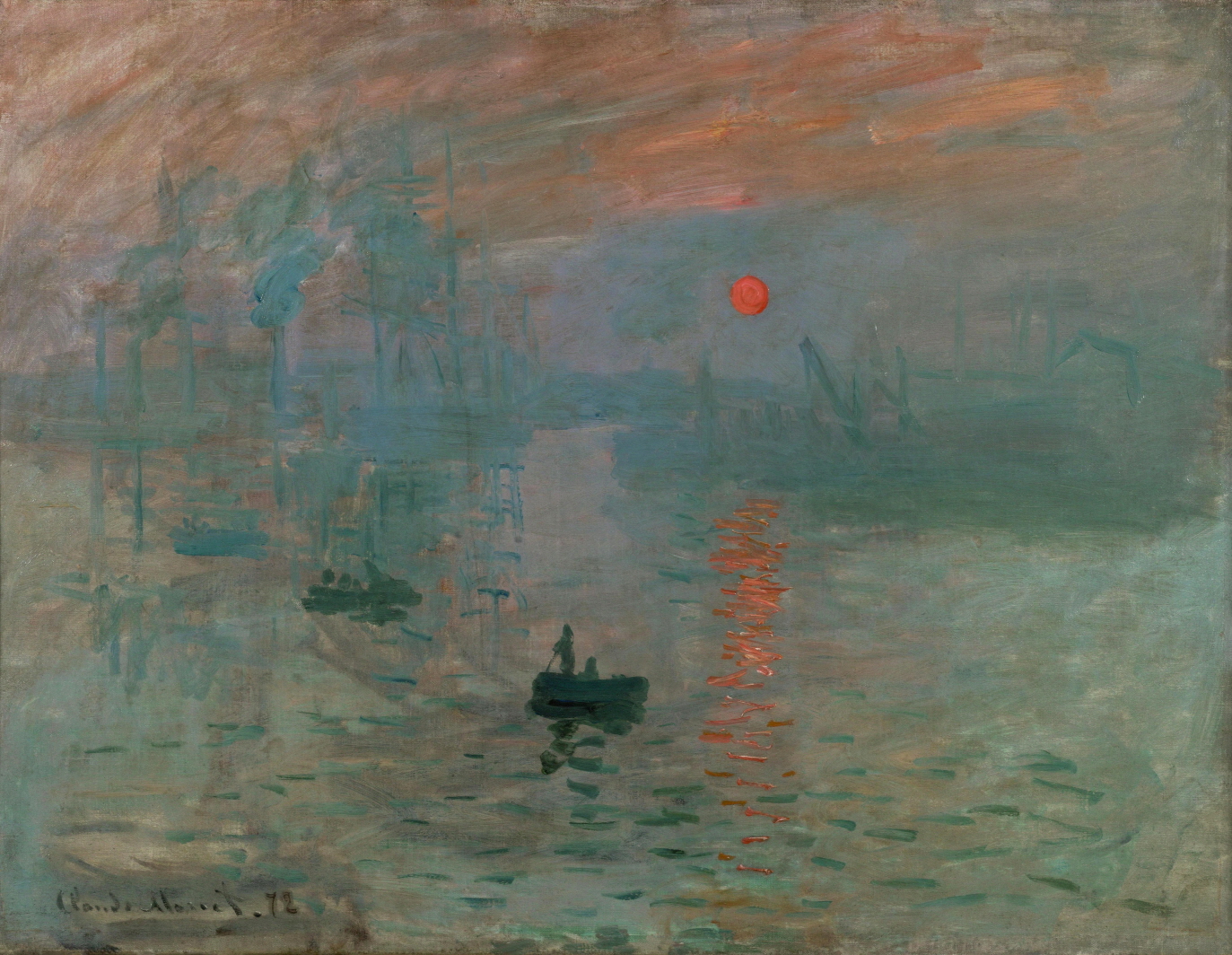

Historically, modernism is often marked by the "French Revolution" (1789). In philosophy, its roots lie in Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (1781), in literature with Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du mal (1857), and in art with Monet's 〈Impression, Sunrise〉 (1872), which is considered the beginning of Impressionism.

Claude

Monet, 〈Impression: Sunrise〉,1872,

Oil on Canvas, 48 x 63cm

Claude

Monet, 〈Impression: Sunrise〉,1872,

Oil on Canvas, 48 x 63cmMonet’s

〈Impression: Sunrise〉

does not depict the shape of the subject but how it appears under light. Before

the 20th century, the ability to paint something as "realistic as

possible" was the key criterion, known as illusionism. However,

Impressionism was based on Newton’s scientific discovery that "the colors

we see are not inherent to objects but wavelengths reflected by light."

Moreover,

with the invention of the camera, which could reproduce subjects more

realistically than painting, depicting subjects became less meaningful. As a

result, after Impressionism, the personal perspective of the artist gained more

importance. Personal perspective here does not mean subjective whim but rather

revealing unseen truths or genuine values through the artist’s vision.

In

Cézanne’s 〈Mount Sainte-Victoire〉 (1895) or 〈Still Life with Apples〉 (1895), the forms are awkwardly deconstructed. This is not because

Cézanne failed to depict the mountain or apples beautifully but because he was

showing how the human eye "perceives" objects. This approach, called

visual perception, later influenced artists like Picasso and Hockney.

(Left) A scene staged with real apples, similar to

Cézanne's still life / (Right) Cézanne's 〈Still Life with Apples.〉

(Left) A scene staged with real apples, similar to

Cézanne's still life / (Right) Cézanne's 〈Still Life with Apples.〉When comparing the two images, Cézanne's work appears somewhat unsettling, with mismatched perspectives and awkward composition, yet each object is clearly defined. This is because Cézanne didn’t paint from a single viewpoint or with a strict perspective, but rather focused on each object as it appeared to his eye.

The year 1945 is often referred to in modern art because of the historical event that shifted the center of art from Paris to New York after the end of World War II. As a result, abstract expressionism, pop art, etc. that developed in New York after 1945 are often referred to as post-war art.

Post-Modern Art

Postmodernism, which expanded globally after the 1980s, reflects a trend

influenced by anti-rationalism and deconstructive philosophy. Unlike Modern

Art, which focused on pure and singular forms, Postmodern Art embraced complex

compositions, objects, and installations.

In

Korea, some texts translate postmodernism as "anti-modernism,"

"beyond modernism," or "late modernism." Since the word

"post" encompasses all these meanings, it’s more appropriate to

understand Postmodern Art through these concepts rather than divide them.

One

of the key concepts of postmodernism is "simulacrum," meaning "a

copy without an original."

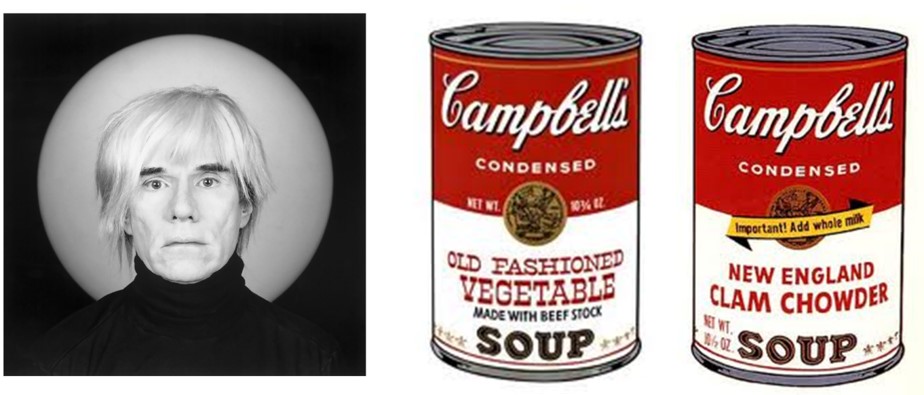

Andy Warhol, 〈Campbell's Soup Cans〉, 1962, MoMA

Andy Warhol, 〈Campbell's Soup Cans〉, 1962, MoMAFor

example, in Andy Warhol’s 〈Campbell’s Soup Cans〉 (1962), the image starts as a product we know but becomes something

entirely new through endless reproduction, detached from its original meaning.

Another

key term is "pastiche," meaning "hybrid imitation." This

refers to borrowing elements from other artists' works and incorporating them

into one’s own. While this sparked debate over originality versus imitation, it

is now recognized as a major expression technique in modern art.

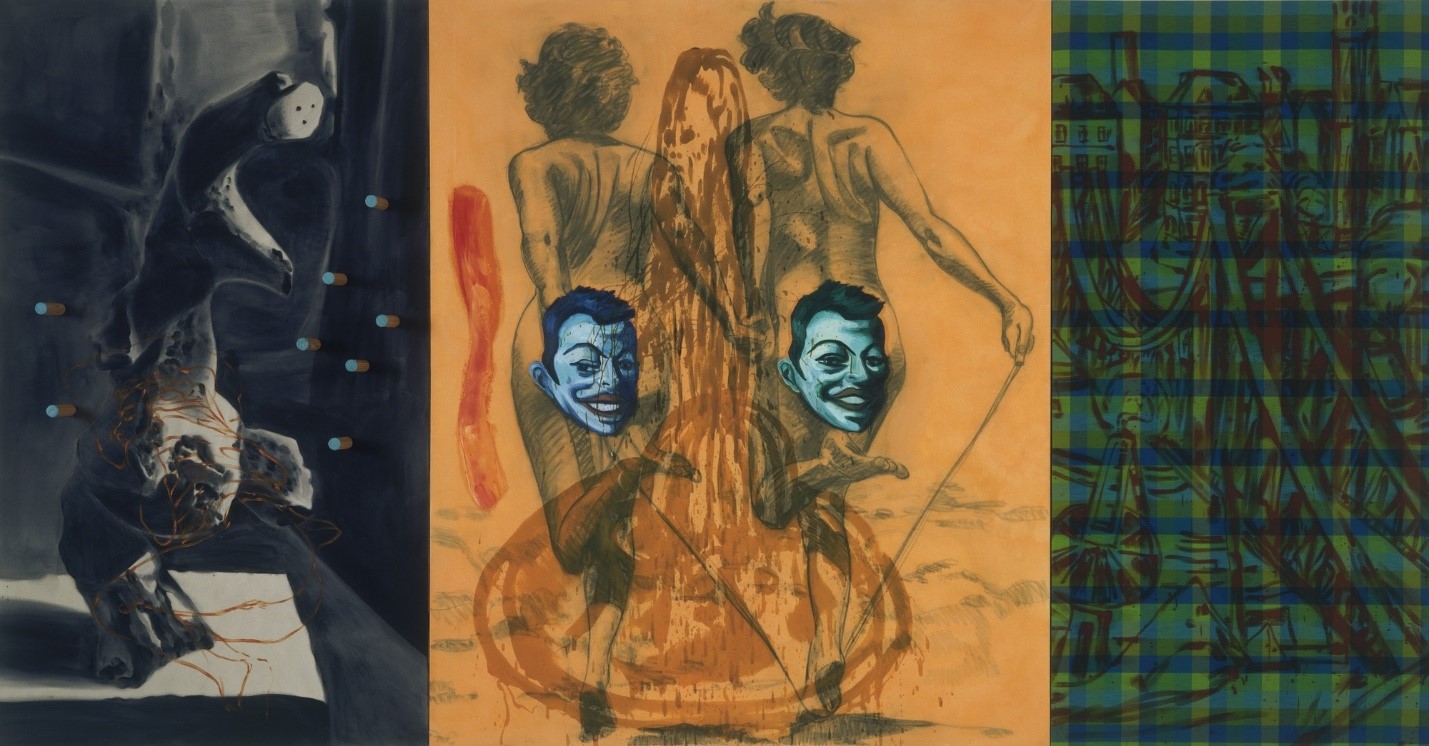

〈Muscular Paper〉, 1985, MoMA Collection

〈Muscular Paper〉, 1985, MoMA CollectionDavid Salle’s 〈Muscular Paper〉 (1985) exemplifies this. The work is divided into three canvases, mixing multiple subjects and techniques.

(Left) Pablo Picasso, 〈Bather〉, 1931, Bronze, Museum Picasso, Paris /

(Left) Pablo Picasso, 〈Bather〉, 1931, Bronze, Museum Picasso, Paris / (Middle) Jusepe de Ribera, 〈The Clubfooted Boy〉, 1642. /

(Right) Max Beckmann, 〈Large Bridge〉, 1922

It

features a photo of Picasso’s sculpture by the French photographer Brassaï, and

a split-face figure from Jusepe de Ribera’s 〈The

Club-Footed Boy〉 (1642). Salle’s appropriation of

others' works asserts that his values stem from diverse sources, emphasizing

the independence of his art.

This

practice of using others' works is also called "appropriation," a key

term in understanding postmodern art alongside simulacrum and pastiche.

Contemporary Art

The term "contemporary" began to be widely used in Western art in the

1970s and has recently been translated as "contemporary art" in

Korea.

Contemporary

art aims to reflect the various issues of our time through new forms,

encompassing all aspects of human concern. It also breaks away from traditional

methods, using a wide range of materials and techniques.

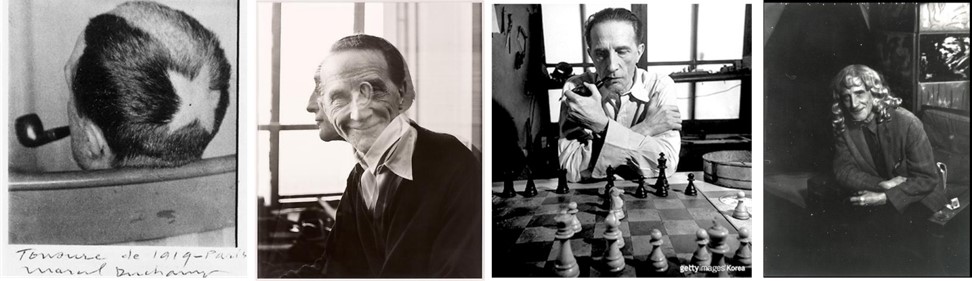

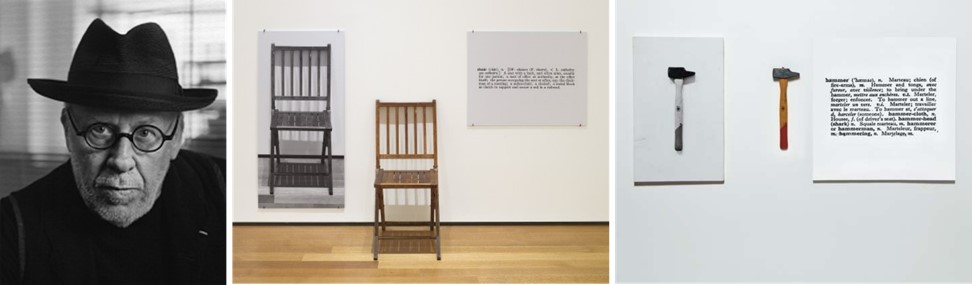

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1967)

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1967)The

beginning of contemporary art can be traced back to Marcel Duchamp's

(1887–1967) urinal piece 〈Fountain〉 (1917). This work, which transformed a mass-produced urinal into

art, is referred to as an "object" (French for objet) and is

considered a groundbreaking piece that shattered the fundamental concepts and

forms of modernism.

While

Monet of Impressionism and Picasso of Cubism employed innovative techniques,

they never stepped outside the confines of the canvas. Duchamp, however, is

regarded as a true revolutionary for completely breaking down that barrier.

(Left) 〈Fountain〉 Photo of Original, 1917 / Rright) 〈Fountain〉, Replica, 1964

(Left) 〈Fountain〉 Photo of Original, 1917 / Rright) 〈Fountain〉, Replica, 1964Joseph Kosuth’s 〈One and Three Chairs〉 (1965) further advanced contemporary art by presenting a chair, a photograph of the chair, and its dictionary definition. This piece shifted the focus to the concept of what constitutes an artwork, opening up a new dimension in art.

(Left) Joseph Kosuth / (Center) 〈One and Three Chairs〉, 1965 / (Right) 〈One and three hammers〉, 1965

(Left) Joseph Kosuth / (Center) 〈One and Three Chairs〉, 1965 / (Right) 〈One and three hammers〉, 1965The

art philosopher Arthur Danto viewed this work as the start of contemporary art,

predicting that as art became more philosophical, it would no longer focus on

beauty or visual representation.

In

2015, the Museum of Modern Art in New York held an exhibition titled “The

Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World”, questioning the

existence of genuine painting in an era of “atemporality.”

Installation view, “The Forever Now”, Works of Kerstin Brätsch, 2015, MoMA

The theme of this exhibition was to question what constitutes genuine painting and how it can exist in an era of "atemporality"—a time when things momentarily appear and disappear, or suddenly emerge from unknown places.

“Installation

view, “The Forever Now”, 2015, MoMA

“Installation

view, “The Forever Now”, 2015, MoMASome of the artists invited to the exhibition

laid canvases on the floor, turned them upside down, or presented materials

that seemed entirely unrelated to painting, claiming them as such. Others

exhibited canvases adorned with neon signs, taking on radical and extreme

forms, which stirred significant controversy even in New York at the time.

Notably, some of the participating artists went on to become stars in

contemporary painting after the exhibition.

Furthermore, contemporary art

demonstrates the infinite potential of human perception by borrowing and

incorporating radical concepts or technologies from all areas of society,

including religion, philosophy, science, politics, and economics, to create

completely new forms of art.

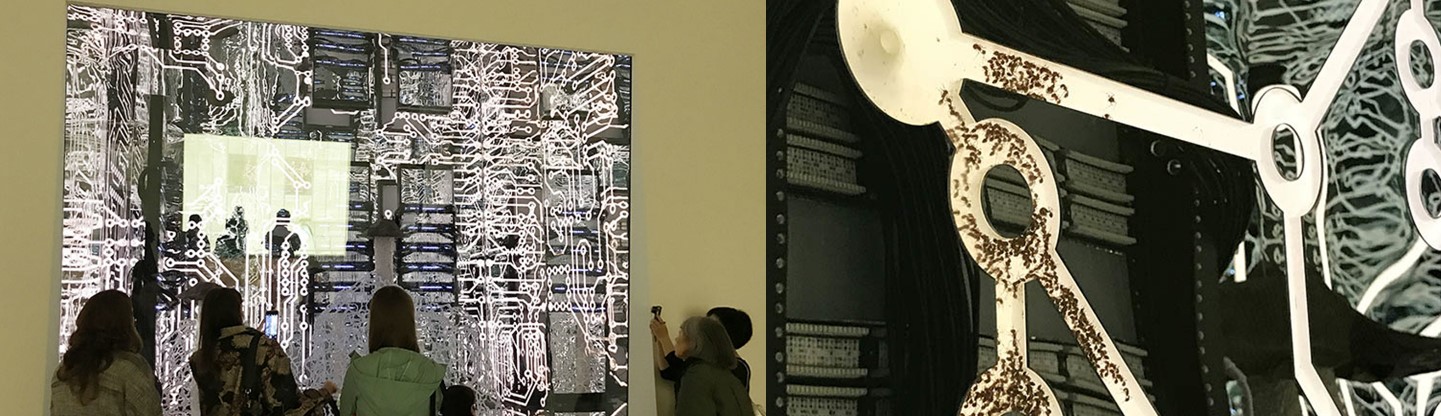

The

Hugo Boss Prize 2016 : Anicka Yi, “Life Is Cheap”, Guggenheim Museum

The

Hugo Boss Prize 2016 : Anicka Yi, “Life Is Cheap”, Guggenheim MuseumKorean-American artist Anicka Yi (b. 1972), who won the 2016 Hugo Boss Prize and held an exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum, showcased works such as “Life is Cheap”. In this exhibition, she crafted an ant colony to resemble an electronic circuit, displaying live ants within it. With the help of a chemist, she also cultivated mold, which grew on objects in the exhibition space, creating beautiful and surreal visuals. Additionally, she presented a piece where visitors could smell the scent collected from specific locations, allowing them to experience human fragrance.

The

Hugo Boss Prize 2016 : Anicka Yi, “Life Is Cheap”, Guggenheim Museum

The

Hugo Boss Prize 2016 : Anicka Yi, “Life Is Cheap”, Guggenheim MuseumJordan Wolfson (b. 1980), who participated in the 2017 Whitney Biennial, exhibited 〈Female Figure〉 (2014) at David Zwirner Gallery. This work combined animatronic technology with the grotesque appearance of a gay male figure in a female body. The figure’s intricate yet disturbing hand movements, along with its unsettling habit of locking eyes with the audience, vividly illustrated how contemporary values and ethics are shifting.

Jordan Wolfson, 〈Female Figure〉, 2014, David

Zwirner Gallery

Jordan Wolfson, 〈Female Figure〉, 2014, David

Zwirner GalleryToday, it has become nearly impossible to view art through a single set of principles or standards. However, this doesn’t mean that the intrinsic truth of humanity or the value of art has disappeared. As Lévi-Strauss said, "Technology and civilization may evolve, but the human spirit and culture do not progress. They simply expand, are seen differently, and are reinterpreted."