As

Zygmunt Bauman observes and explains in an extrasensory manner, the

contemporary society is liquid in its characteristics. The rigid social

standards and ideologies have been collapsed as if they were melted down, and

the absolute standard has lost its authority. The foundation and boundary

disappear as they become liquid, and diverse fields and values cross and

influence each other. Everything truly has become liberated.

On

the other hand, the flexible autonomy of liquidity has increased the

instability of the society. The power to resist has also become liquid, causing

a number of individuals to bear such an unstable state. However, many

contemporary artists have been staying in a liquid state and pursuing unrefined

circumstances. They are resisting the instability of the era of liquidity and

the new authorities of this time in different ways.

Installation

view of “FROM HEAD TO TOE” ©P21

Installation

view of “FROM HEAD TO TOE” ©P21In

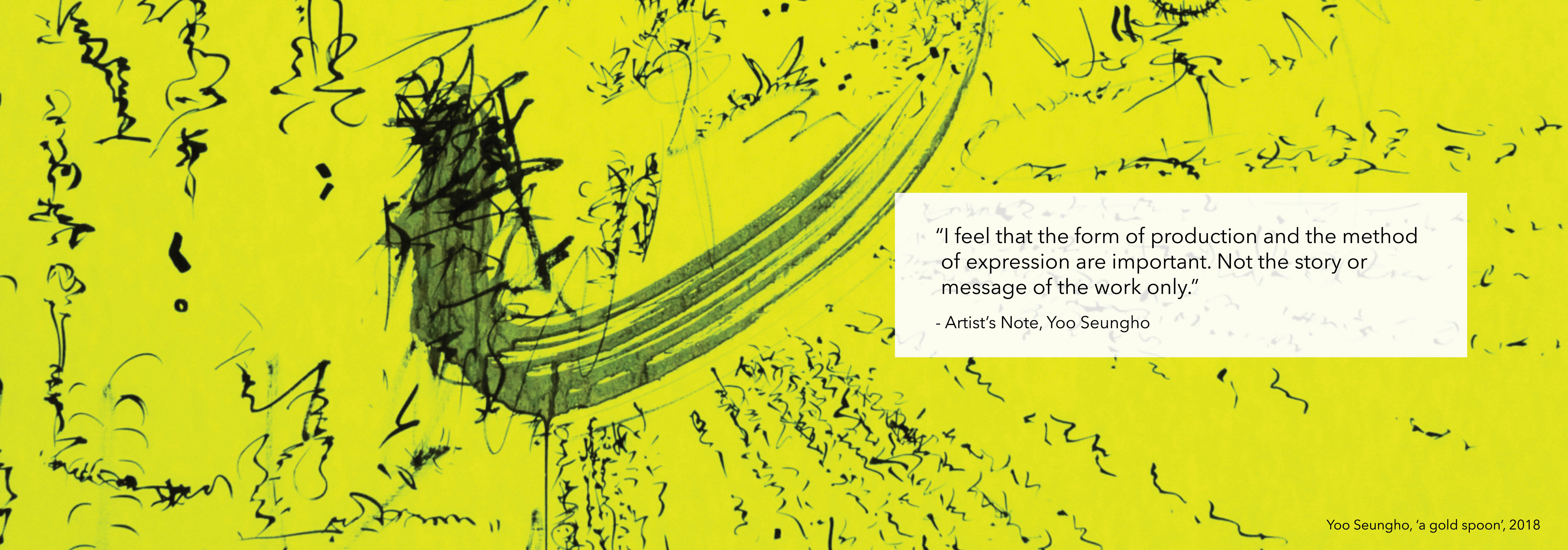

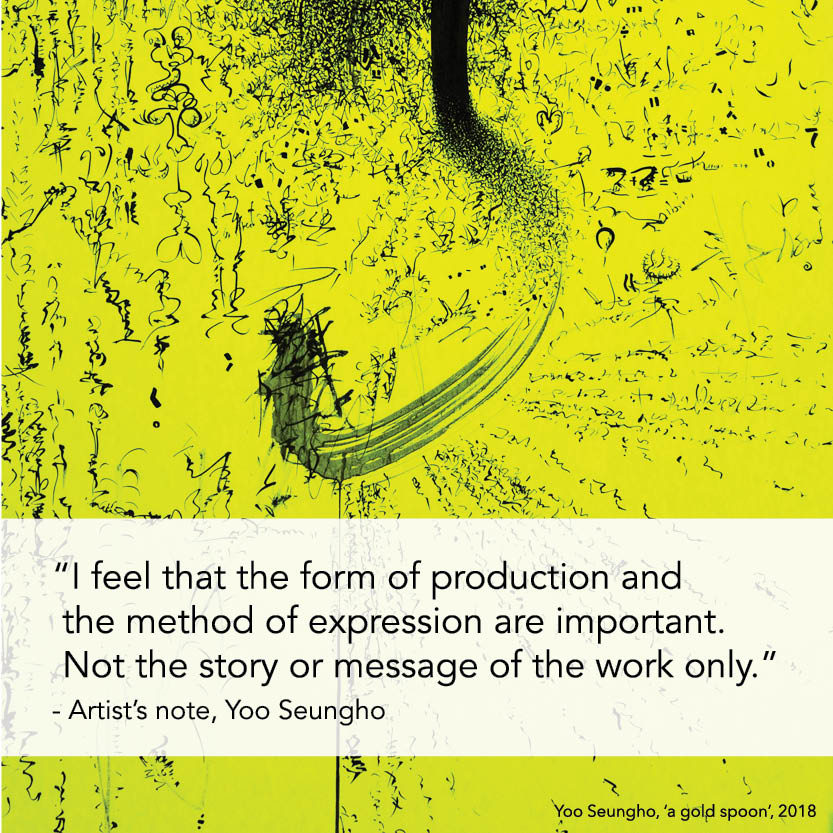

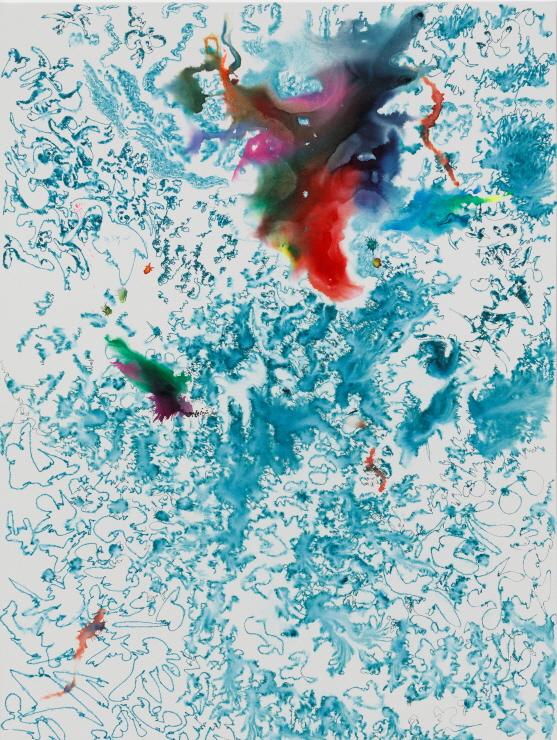

YOO Seungho’s work, the liquidity of the contemporary society is strongly

present. Although the artist deals with firm and concrete forms such as letters

and images, two contrasting elements cross and change into each other while the

composition of the canvas is as liquid as fluid. The word ‘뇌출혈’(cerebral

hemorrhage) becomes ‘natural,’

and ‘natural’ becomes a figure

of a mountain to form a sublime landscape where a part of the canvas becomes a

bird before anyone recognizes and flies away towards the other end of the

canvas.

Most

of the images flow down toward the bottom of the canvas, becoming a surrounding

landscape where the common people stand. The movement also operates in the

opposite direction. Most of the previous criticism on YOO’s work focused on the

relationship between letters and images in his work. However, there are many

more contrasting relations lurking in his work. There are an array of deficient

substances, such as different languages, tradition and modernity, poem and

painting, meaning and figure, abstraction and figurativeness, surface and

depth, and expression and confession, which are elements that construct YOO

Seungho’s canvas. Although these elements are often read as a wordplay, playful

scribbles, or a way of presenting humor, one can observe how painted letters or

images change and are transformed into the other, which leads to a realization

that such a process seems natural as if it was done as an inevitable phenomenon

than an unnatural attempt intended by the artist.

Such

a process seems to be contained within different elements as if a larva becomes

a moth which then lays eggs. Different elements seem to be moving toward each

other while bearing the fundamental deficiency inside them as in the

relationship between oneself and the others, lovers, or ultimately life and

death. In this sense, the artist seems to satisfy the demand and deficiency of

letters and images that struggle to become the other on the canvas while he

blankly gazes them and uses his brush at a proper timing.

Installation

view of “FROM HEAD TO TOE” ©P21

Installation

view of “FROM HEAD TO TOE” ©P21In

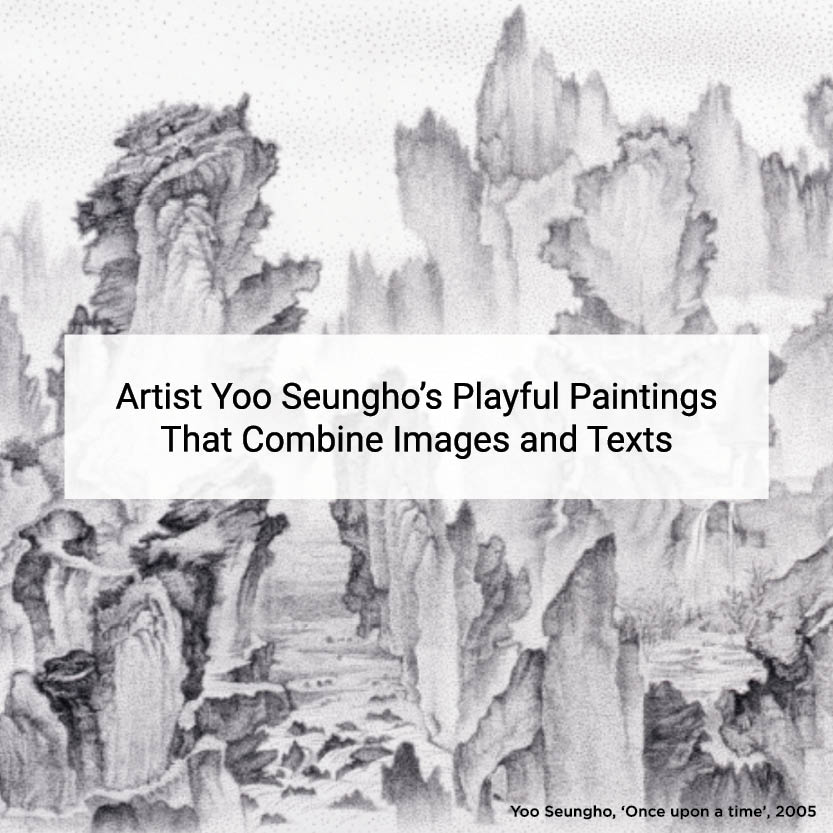

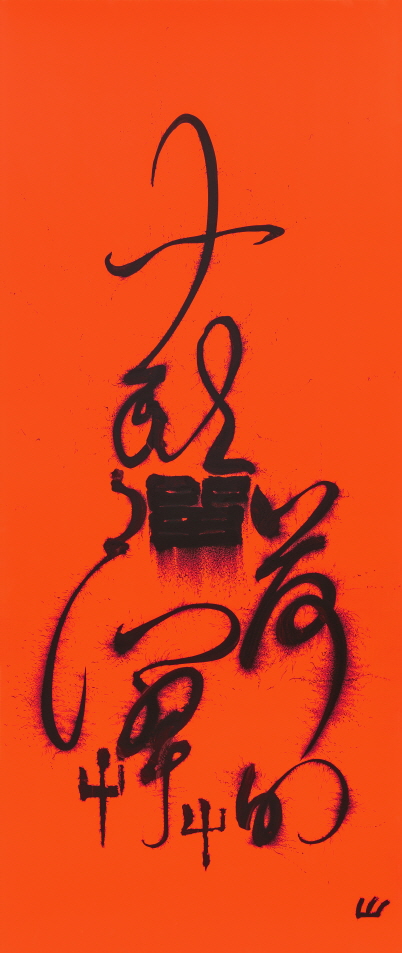

the current exhibition From Head to Toe, most of the works are paintings have

letters in a cursive style. The transition from the style of pen writing to

that of brush writing deserves a notable attention. It is true that the artist

used the same style in his previous solo exhibition Shaking Your Hair Loose

(Perigee Gallery, 2015). His 2005 work I go also showed a glimpse of the style.

However, a series of works that employ brush writing started in a work titled

Ddeok♨ (2015), a work exhibited in The Tradition is the Future (Ilju &

Seonhwa Gallery (now Sehwa Museum of Art), 2016). The work appropriates the

writing style called Haengcho(行草) from HAN Seok Bong, a

calligrapher from the mid-Joseon period. After the exhibition, YOO started

employing brush writing as a major component of his work. In fact, this change

seems to be a natural progression of his artistic style since most of his

previous works share similarities with the style of cursive writing.

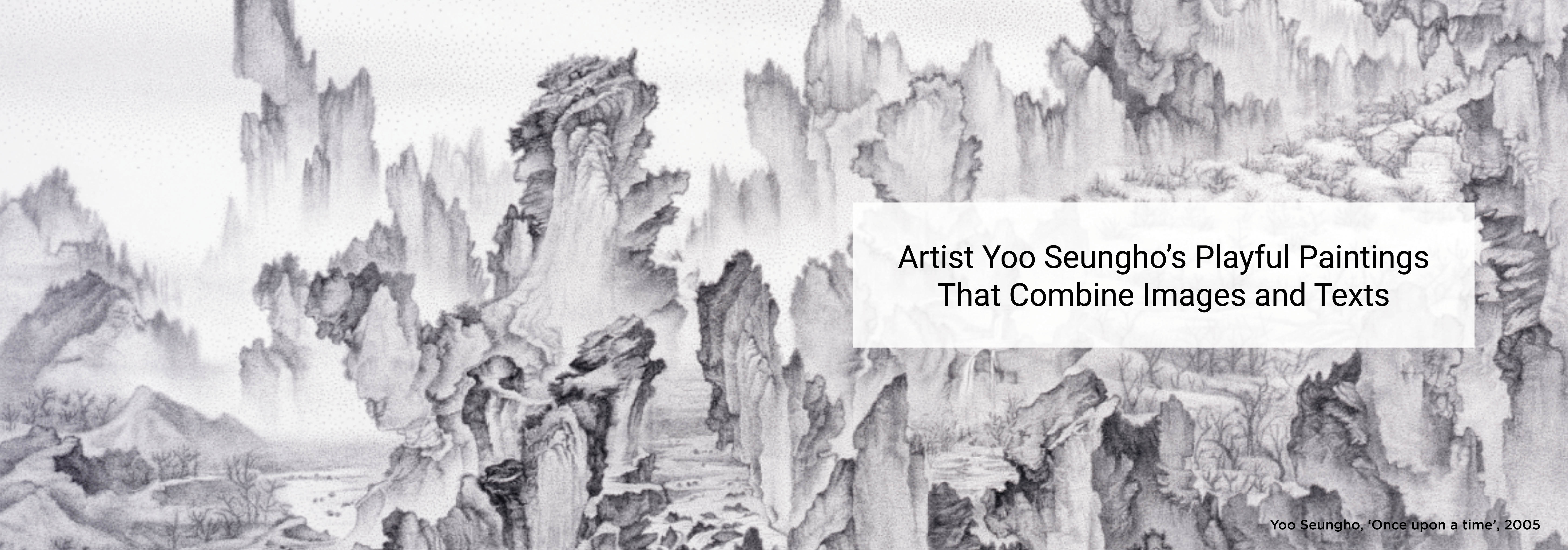

Moreover,

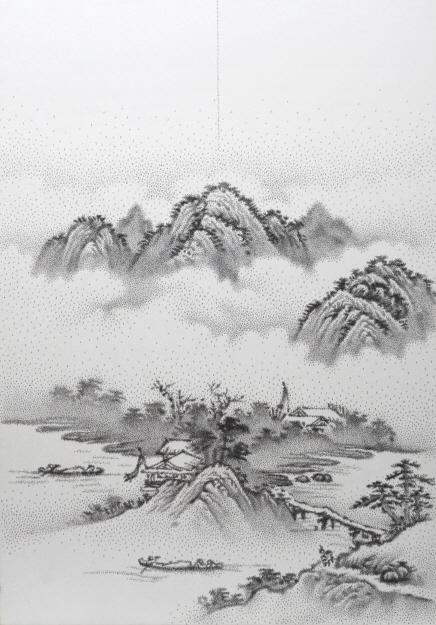

YOO produced many works that copied paintings by Guo Xi (郭熙) or Fan

Kuan (范寬) from the Northern Song Dynasty period. The

cursive writing style also appeared in the same period of these artists. With

an intention to better express the energy embedded in letters, the artist made

a primary sketch where the overall shape and composition were modified from the

original writing by enlarging and moving certain strokes. He then painted the

sketch on a large rice paper. The dance of thin lines was static yet vigorous

to resemble a movement made by a dancer, leading to an impression that the

energy contained in the cursive writing of HAN Seok Bong was completed in full

by YOO Seungho. The artist confessed that he himself felt strangely excited and

captivated while he hung Ddeok♨ for about a month on a

wall in a good light after completing the work. After listening to the story,

what the artist confessed does not seem to be that strange. Rather, it is

possible to see that such a strange feeling became a motive to start the series

of works that employ brush writing.

Installation

view of “FROM HEAD TO TOE” ©P21

Installation

view of “FROM HEAD TO TOE” ©P21In

fact, letters written in the style of cursive writing are closer to images than

letters. As the name of the style (草書, which literally means

grass and letter) came from its similarity with the shape of grass, it is a

matter of course. Letters written in the cursive style are both liberated and

dynamic. As well known, one of the basic principles of Chinese character is

hieroglyphic composition. For example, ’象’ (elephant)

takes the shape of the animal. ‘草’ (grass)as a radical

‘艹’

that indicates grass or plant when it is combined with other characters. Thus,

since Chinese characters are an abstraction of figurative shapes, there is no

difficulty in conveying any meaning if a letter is close to the image of its

original reference, regardless of how cursive the letter is written. What

should stay intact is the shape of the letter itself, though.

Whether

it was Huizong (徽宗) of the Northern Song Dynasty, Chusa (秋史)

and Seok Bong (石峯) of Joseon period, those that favored

the cursive writing style understood that they could come close to the essence

of writing ironically by scribbling the letters down. One can also say that

they were artists that were confident enough to do so. And YOO Seungho also

gives that sense of confidence. The confidence has been shown in what he wrote

on his canvases, distorted figures in his works, daring depictions of erotic jokes

that one might observe in obscene pictures (春畵, a

particular term for erotic paintings produced during Joseon period), and rather

indifferent titles he made for static landscape paintings, which reminded of

his way of speaking. The current series with the cursive writing style shows

more of that confidence. In the works in the series lie energies that are

tranquil yet bold and feeble yet massive that one can feel from the back of a

farmer who finished his job during the day and riding an oxcart or a smell of

earth from the traces of moving on a ridge between rice paddies. Such energies

are beautifully conveyed on the canvas as if it was done by a person full of

confidence in a relaxed manner.

A

poet and a scholar of Korean literature CHO Ji Hun once mentioned that the

Korean aesthetic consciousness can be found in the notion of ‘멋’ (Meot),

which means sapidity, taste, or a general appreciation of beautiful things and

actions. CHO finds Meot in lines that are curved rhythmically, distorted

shapes, and optimism that consistently sustains humor. Further, CHO tells that

the authentic meaning of the term is seen in the ‘beauty

of transcending formality’ (超格美),

which is “a formality that enters and escapes from a

formality.” In this sense, the cursive writing is the

most appropriate form to express the beauty of transcending formality since it

is to mimic shapes to create letters that transcend the given frame and even

become figures that contain movement.

Installation

view of “FROM HEAD TO TOE” ©P21

Installation

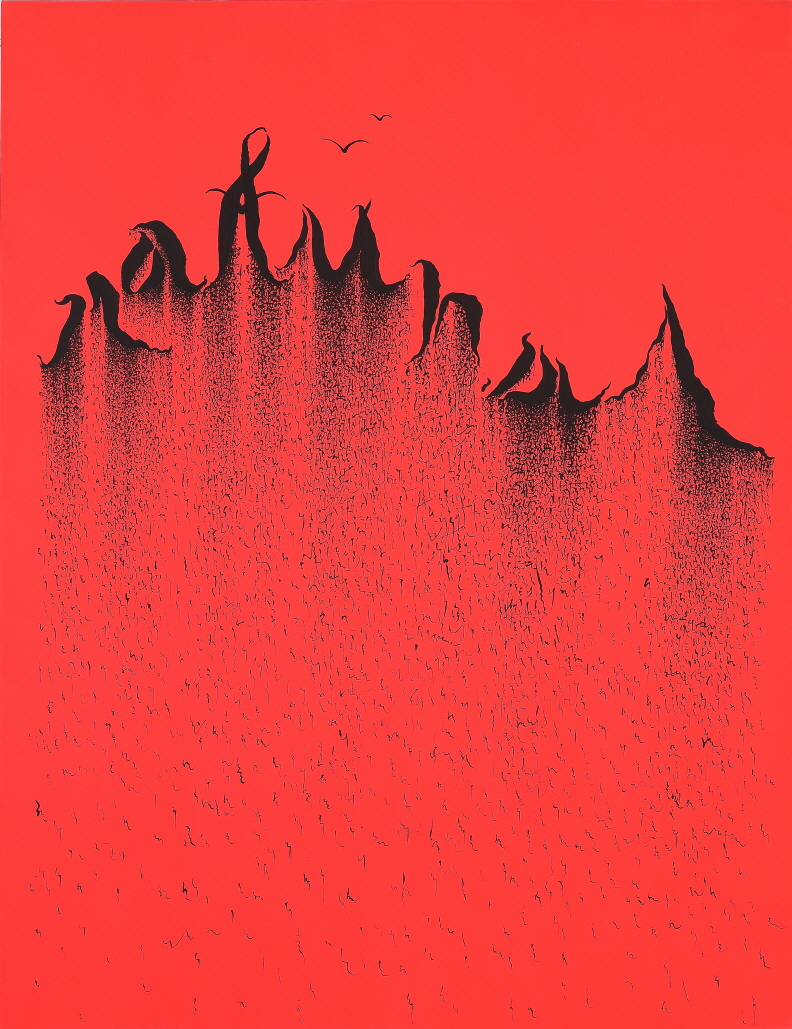

view of “FROM HEAD TO TOE” ©P21“Lies behind the mask, the path.” The line is from HWANG Ji Woo’s

poem “503.” I wrote it down while I was listening to a statement made by an

aesthetician where he quoted the poem. I was reminded of the line when I was

observing YOO Seungho’s fool (2017). What catches one’s eyes in this long

neon-colored canvas that stretches more than three meters is a letter ‘屮’

(grass). It is the same letter that Chusa wrote for a signboard hung at the

entrance of Dasan Chodang (茶山草堂, a residence building used by JEONG Yakyong (1762-1836) during his

exile (1800-1818)).

On

the signboard, the letter for grass is written straightly to remind of a

trident while the letter signifying a mountain is tilted like a piece of rice

cake while it is supposed to be grandiose. This can be an allusion of the ruler

and the exile, but what is also evident is that the letters are a clear

expression of the people and their potential power. In addition to grass, YOO

Seungho’s canvas is composed elegant lines that are both thin and thick,

conveying the strength and weakness of force. Strokes of thin lines follow the

elegant lines, forging an imagery of grass that provides a space to the path

that has been followed by a brush. Lines that deviate from the standard shape

of letters become paths by the artist’s brush strokes. To find zen hidden in

emptiness shall be more difficult than finding it from visible forms.

When

I asked the artist about why he started using brushes instead of pens, he gave

this response. “Now is the time to use brush writing.” If a path is laid in

front of oneself, one should follow the path. The path might be of following

the tradition or being adapted to the society. However, there is no fixed path

from the start. If a painter has faith in himself and follows his way, a path

shall be paved. YOO Seungho overcame an immense pressure he felt as an artist

and is now paving his path toward becoming a seeker of truth. And this might be

a reason I strongly sensed liquidity as I observed works in the exhibition

including fool. In YOO Seungho’s work, the new authority born in the age of

liquidity and the simple and pure movement of the common people that resist

that authority turn the canvas into a state of liquidity.